In her chapter “Race and the American Gothic,” Ellen Weinauer defines the important (and sometimes problematic) role of race in American gothic literature:

“In the US context… the Gothic tells the “true” story of race in America- a story that points not only to the existence of substantive national “unfreedoms” but also of the strenuous effort to create racial categories that distinguish free, from unfree, civilized from savage, white from black.” (86)

Based on this quote, texts within the American gothic tradition have put forth radical and regressive points of view when discussing the issue of race. It is through this cacophony of divergent racial representation within American gothic texts that we can, according to Weinauer, better understand “the “true” story of race in America.”

It’s vital for gothic scholars to remember that, although the gothic mode is unique in its incredible ability to give voice to the repressed, gothic literature can still contain “regressive attitudes to gender, ethnicity, and class” (Blake & Soltysik 3). As much as I adore this genre and mode, it is for this reason that I’m careful to not ascribe too much to gothic utopianism.

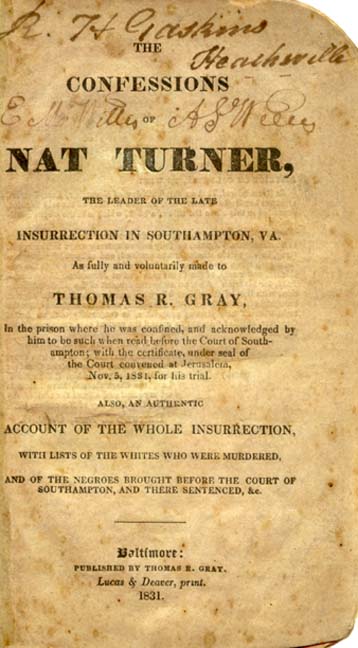

Today, I wanted to look at how two texts dealing with slave mutinies represent race in America through gothic tropes and language: Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno” and Thomas Gray’s “The Confessions of Nat Turner.” The two texts both represent race through the gothic, however, they do so very differently.

It is maddeningly difficult to determine what Melville’s stance is towards slavery in “Benito Cereno.” His story tells of a violent and terrifying slave revolt aboard the Spanish ship, the “San Dominick.” The two primary white characters are the over-indulgent yet heroic American Captain Amasa Delano and the weakened Spanish captain Don Benito Cereno. The story is told through the third person limited, meaning that the reader follows Captain Delano closely. As we read through the text, we only know just as much as Delano, which is often not much. Both the sympathetic representations of Delano and Cereno, as well as the narrative choice, cause Melville’s white characters to be more relatable to his readers (who he probably imagined to be white), while his black characters are unknown and othered. Through Delano’s observations, we see the slaves aboard the San Dominick as mysterious and curious pieces of cargo rather than individual humans.

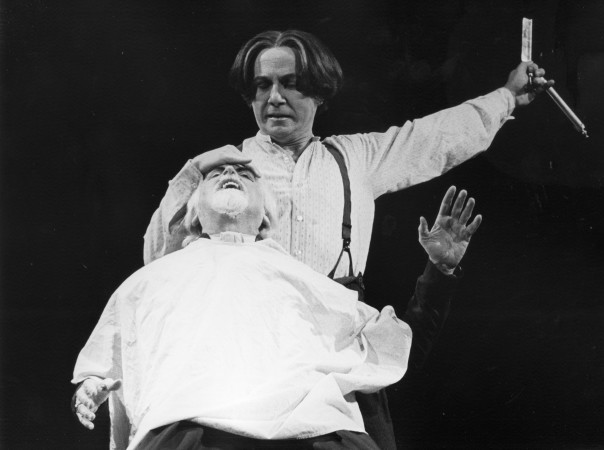

In his frequent “flashes of revelation” and at the end of the narrative, however, Delano views these characters as something more violent: monsters. While watching Babo shave Don Benito, Delano imagines a different scene: “…nor, as he saw the two thus postured, could he resist the vagary, that in the black he saw a headsman, and in the white, a man at the block” (100). Near the end of the battle between his ship and the mutinied San Dominick, the black rebels are described: “Their red tongues lolled, wolf-like, from their black mouths” (120). Ellen Weinauer labels this gothic view of the racial other “monsterizing” (88). By claiming that those of African descent were monstrous and less than human, white Americans could justify slavery existing in a nation dedicated to freedom. Thus, gothic texts that engage in the monsterizing of racial others support both the cultural lie that protects slavery, and therefore, slavery itself.

I had a difficult time resisting “flashes of” Sweeney Todd while reading the shaving scene…

That being said, Melville does work against prominent racial theory of his day. Weinauer describes the nefarious work that race theorists performed in the 18th and 19th centuries in order to protect the economically and politically powerful institution of slavery (89). They insisted that whites were “in essence” superior to other races and claimed that black people were naturally docile and obedient (ibid). In “Benito Cereno,” this pseudo-scientific school of thought is revealed to be a lie. Despite his brief “flashes of revelation,” Delano is unable to realize that a mutiny had occurred upon the San Dominick until it is clearly and graphically performed before him when Babo moves to stab Don Benito in the heart. Delano misunderstands most of the weirdness because he subscribes to the racial theory of his day. He believes that Babo won’t leave Cereno’s side because of his natural obedience, not because of his desire to constantly threaten the Spanish captain. Babo is ultimately revealed to be the “ringleader” (123) of the entire plot. This means that he and the rest of the slaves on board were able to trick the white Captain Delano, proving the myth of racial inferiority to be nothing more than a myth.

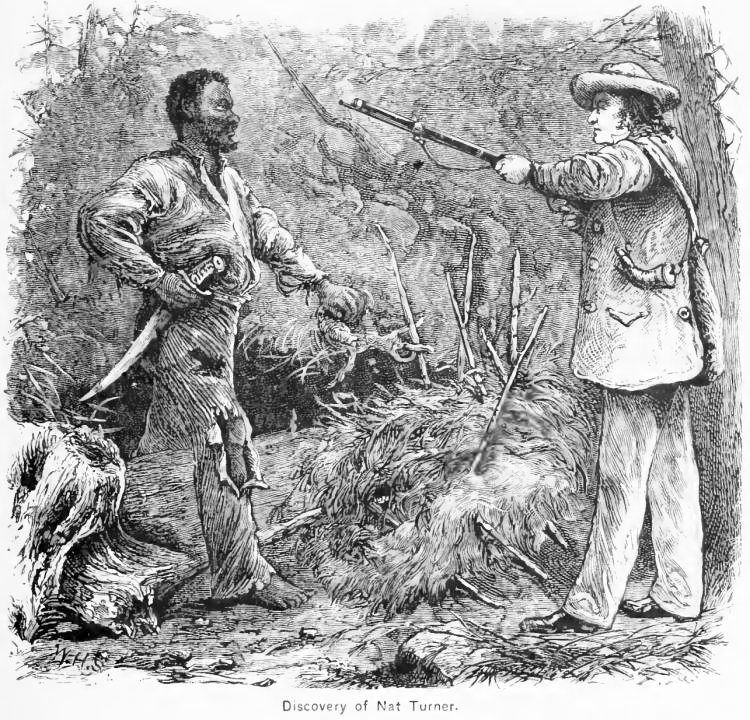

Thomas Gray injects gothic imagery into “The Confessions of Nat Turner” for less ambivalent reasons. While it may feel difficult to detect Melville’s stance on slavery by reading “Benito Cereno,” Gray’s opinion is very clear. The entire confession, which is supposedly completely faithful to Nat Turner’s narration of the events, is replete sensationalized and graphic depictions of the murders committed during the slave uprising led by Turner. In these descriptions, Gray makes sure to take part in the national project of monsterizing racial others. He describes Turner and his fellow rebels as “diabolical actors,” a “ferocious band,” “ferocious miscreants,” “monsters,” and “barbarous villains.” Gray further claims that Turner related the entire tale with a “fiend-like face… still bearing the stains of the blood of helpless innocence about him… I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.”

Gray’s description of Turner in his preface to the confession is particularly gothic. He contrasts the “calm and peaceful aspect” which Turner presented to the public before the rebellion to the “gloomy fanatic” that was “revolving in the recesses of his own dark, bewildered, and overwrought mind.” The act of peering below the seemingly normal surface to discover the dark underbelly festering beneath is common within gothic literature.

By imbuing his non-fiction text with generic elements familiar to popular gothic fiction, Gray created a text which could deeply impress the minds of his (white) public. Even if his readers were not conscious of the inclusion of the gothic, its presence is still felt and is still important. “Confessions of Nat Turner” worked to continue the monsterization of black Americans. Gray repeats his belief that Turner’s motive for the crime was nothing more than religious “fanaticism.” The desire for freedom is never clearly mentioned. Gray also highlights the fact that Turner’s master was “too indulgent.” His text presents a racist argument not only for the continuation of slavery, but its strengthening. According to Gray’s presentation, without strict laws and enslavement, racial others could perform monstrous deeds similar to the Turner Rebellion.

Works Cited

Blake, Linnie and Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet. “Introduction: Neoliberal Gothic.” Neoliberal Gothic, edited by Linnie Blake and Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet, Manchester University Press, 2017. pp. 1-18.

Gray, Thomas. “The Confessions of Nat Turner, The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, VA: Electronic Edition.” Documenting the American South, 1999.

Melville, Herman. “Benito Cerino.” Billy Budd, Bartleby, and Other Stories, edited by Peter Coviello, Penguin Books, 2016. pp. 55-137.

Weinauer, Ellen. “Race and the American Gothic.” The Cambridge Companion to American Gothic, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Cambridge University Press, 2017. pp. 85-98.