Background

Our Mutual Friend was originally published serially from May 1864 to November 1865, but was published in two volumes in 1865. It is Dickens’s last complete novel and contains an incredibly complex plot with a huge cast of characters. Some of Dickens’s contemporary reviewers, in fact, found the plot too complex and not very well organized. The Times of London, for example, claimed that the first few chapters did not effectively draw the reader into caring about the characters. However, some critics hailed the work, including The New York Times. In the Times‘s November 22, 1865 issue, it is conjectured that “By most most readers… the last work by Dickens will be considered his best.”

Plot Summary

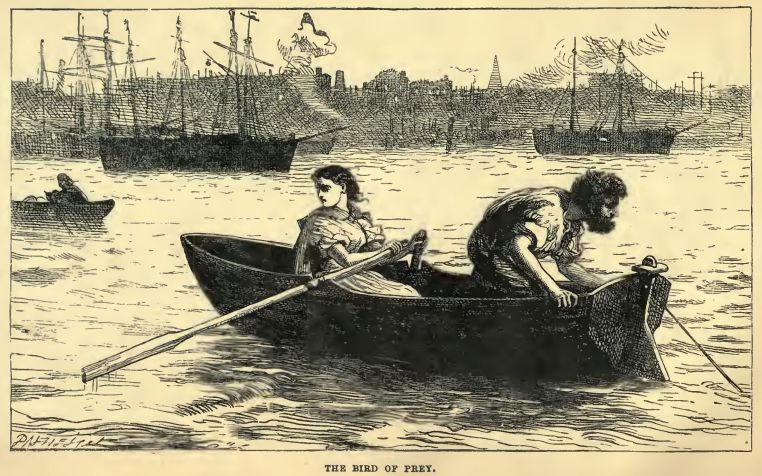

The plot begins on the river Thames, with boatmen fishing out the night’s corpses. John Harmon (our mutual friend) is returning to England after the death of his father, a successful and wealthy “dust contractor.” Harmon’s father left a very strange will: in order to inherit his fortune, his son must first marry Bella Wilfer, a girl who John Harmon had never met. John foolishly tells a sailor on board the ship all about his will, as well as his plan to take on a false identity once in London in order to properly decide whether or not he wishes to marry Bella. The sailor attempts to kill John, but fails so horribly, in fact, that the sailor dies instead. The sailor’s body is later found by the boatmen, who believe the body to belong to John Harmon due to the will found in the corpse’s pocket. Once on land, John takes on the identity of John Rokesmith and becomes employed as secretary to Boffin, the elder Harmon’s employee who has since inherited the Harmon fortune and lucrative dustheaps due to the belief that the younger Harmon was dead. Mr. and Mrs. Boffin adopt Bella who becomes obsessed with wealth, claiming that she will only marry for money. She rejects Rokesmith’s offer of marriage. Silas Wegg, a one-legged stall-keeper and “literary man,” along with Mr. Venus, a taxidermist, attempt to blackmail Boffin. Boffin discovers Rokesmith’s true identity, and works with him to secure Bella’s heart. He does this by behaving like a miser so that Bella may discover how money can corrupt. Bella falls in love with and marries Harmon (still as Rokesmith). After their first child, Harmon finally reveals to Bella his true identity, as well as their fortune. A secondary story line runs alongside this plot: Lizzie Hexam, the daughter of a boatsman, is the object of two men’s love: the teacher and friend of Lizzie’s brother, Bradley Headstone, and the handsome young lawyer, Eugene Wrayburn. Lizzie prefers Eugene, but feels she cannot marry him due to their difference in class and his idleness. Madly jealous, Headstone attempts to murder Wrayburn, but fails. Lizzie nurses Wrayburn back to health, he is transformed into a man worth loving, and the two get married. Headstone is blackmailed by Rogue Riderhood, who has proof of his attempt at murdering Wrayburn. The two die by drowning after struggling together beneath the Thames. 1

Mr Venus’s shop

Notes & Quotes

- I am particularly interested in the capital flows of this novel. First, a great deal of fortune comes from the Harmon dustheaps (which, according to The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction, may “in fact be a euphemism for ‘excrement'” (484)) and the boatmen are able to make a living off of the dead human bodies they find in the river. Mr. Venus also holds a business and performs his “art” of taxidermy using animal and human body parts. In Our Mutual Friend, money can also buy large portions of a person’s life. When Mr. Boffin discusses the terms of employment with John Rokesmith (aka John Harmon), he uses very interesting language:

-

‘Then we put the figure,’ said Mr. Boffin, ‘at two hundred a year. Then the figure’s disposed of. Now, there must be no misunderstanding regarding what I buy for two hundred a year. If I pay for a sheep, I buy it out and out. Similarly, if I pay for a secretary, I buy him out and out.”In other words, you purchase my whole time?”Certainly, I do. Look here,’ said Mr. Boffin; ‘it ain’t that I want to occupy your whole time; you can take up a book for a minute or two when you’ve nothing better to do, though I think you’ll a’most always find something useful to do. But I want to keep you in attendance. It’s convenient to have you at all times ready on the premises. Therefore, betwixt your breakfast and your supper- on the premises I expect to find you.’The Secretary bowed. (437-8)

Immediately after this exchange, Mr. Boffin also encourages Bella to marry for money, because her beauty is “worth” something:

-

‘…You are right. Go in for money, my love. Money’s the article. You’ll make money of your good looks, and of the money Mrs. Boffin and me will have the pleasure of settling upon you, and you’ll live and die rich….These good looks of yours (which you have some right to be vain of, my dear, though you are not, you know) are worth money, and you shall make money of ’em. The money you will have will be worth money, and you shall make money of that too…’ (439-40)

This presentation of capital flowing from human bodies (the dustheaps including, if they are to be interpreted as excrement) and capital acquiring human bodies is fascinating and still relevant today. The haunting presence of money as an unseen yet powerful force controls most of these characters. Bella is one of the victims of money until she is taught to ashore money’s vile influence. Only after she is trained to fear it can she be trusted to enjoy it without it blighting her ideal self. Does this novel do the same work on the reader? How is escape from this system of invisible capital possible? Can it only be managed through secret training such as was performed on Bella? How is John Harmon so above it? How is Boffin?

“Bella righted by the Golden Dustman”

I also wonder how this might connect to Jane Elliott’s conception of our present microeconomic mode and the prevalence of the “survival game” subgenre. In order to get out of the capitalist system, Bella had to be placed into a game of which she was not aware. Thankfully for her, she played it correctly and “won.” Much like the survival game subgenre of contemporary pop fiction, Our Mutual Friend’s game on Bella helped her to become a better person and allowed her to step out of the network in which invisible capital holds sway over all human behavior and bodies.

- The prevalence of human body parts, corpses, and dismemberment (the one-legged Silas Wegg who desperately wants to purchase his amputated leg, the life time that is separated from Rokesmith/Harmon when he is employed as a secretary, and Bella’s self-declaration that she would not sell of her sense of morality for any price) seems to fit well with David McNally’s Monsters of the Market. One popular concern during the industrial era was the selling of one’s time to work as an easily-replacable laboring body. Foucault’s work on the selling of one’s labor power might be helpful here. Also, Marx’s vision of capitalism as a vampire which sucks the blood (a form of dismemberment) from the laborer might also help.

Lizzie and her father search for bodies along the Thames

- The role of water in Our Mutual Friend is pretty ecogothic. There are multiple instances of human death occurring within water: the opening scene in which bodies are fished out of the Thames, the attempted murder of Wrayburn occurs on water, and Headstone is drowned by Riderhood, resulting in mutual death. Mr. Venus receives some of his wares from sailors returning along the Thames.

- This summary largely comes from The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction (484-85). ↩