Background

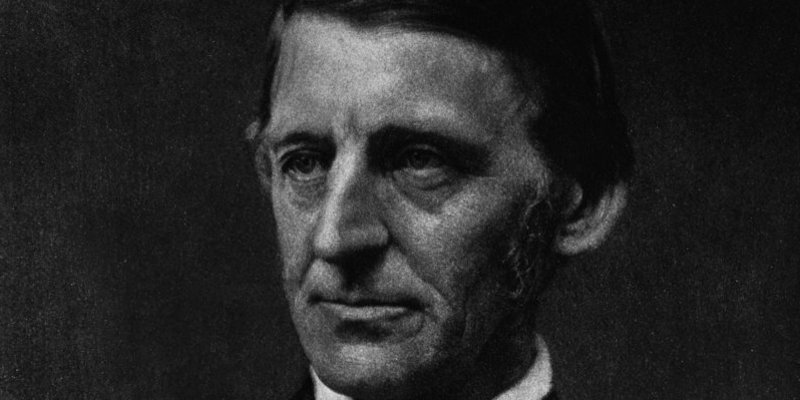

“Experience” is an essay written by Ralph Waldo Emerson, published in his 1844 volume Essays: Second Series.

Summary

Emerson argues against the over-intellectualization of life, instead preferring to experience life in the moment. He also urges readers to be more individualistic, to listen to themselves and their own minds rather than obey and conform to society’s standards. For Emerson, if someone wants to be happy and live a truly correct life, they must have a more embodied and self-self-sufficiant attitude. In particular, he rails against utopian experiments, naming “Education Farm” as one of these problem communities. “Education Farm” is probably a reference to Brook Farm, which was the utopian community to which Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family once belonged.

Notes & Quotes

- Part of Emerson’s argument against overt-thinking seems to spawn from his position within the industrial age. How are individuals able to truly live in the moment and experience their “genius” if everything must follow a strict schedule and deadline? How do we resist becoming automatons and remain as human?

-

So much of our time is preparation, so much is routine, and so much retrospect, that the pith of each man’s genius contracts itself to a very few hours.

- There is a moment in which Emerson discusses his grief over the loss of his son, Waldo. Emerson writes,

-

Grief too will make us idealists. In the death of my son, now more than two years ago, I seem to have lost a beautiful estate,- no more. I cannot get it nearer to me. If tomorrow I should be informed of the bankruptcy of my principal debtors, the loss of my property would be a great inconvenience to me, perhaps, for many years; but it would leave me as it found me, -neither better nor worse. So is it with this calamity: it does not touch me; something which I fancied was a part of me, which could not be torn away without tearing me nor enlarged without enriching me, falls off from me and leaves no scar. It was caducous. I grieve that grief can teach me nothing, nor carry me one step into real nature.

In Emerson’s view of spiritual economy, the cost of his son’s death surprisingly yielded the lowest possible returns: nothing. This passage stands out to me in this essay, because I’m not entirely sure how it fits. Is this to show how self-sufficient each individual is at his or her core? That even the loss of those closest to us cannot fully destroy us because we are truly separate individuals?

- Emerson also focuses on the sensual, embodied experience of life as opposed to the intellectual. He uses Brook Farm as his example of how intellectualized life is nothing if it has no bodily component.

-

What help from thought? Life is not dialectics. We, I think, in these times, have had lessons enough of the futility of criticism. Our young people have thought and written much on labor and reform, and for all that they have written, neither the world nor themselves have got on a step. Intellectual tasting of life will not supersede muscular activity. If a man should consider the nicety of the passage of a piece of bread down his throat, he would starve. At Education-Farm, the noblest theory of life sat on the noblest figures of young men and maidens, quite powerless and melancholy… Do not craze yourself with thinking, but go about our business anywhere. Life is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy. Its chief good is for well-mixed people who can enjoy what they find, without question. Nature hates peeping… We live amid surfaces and the true art of life is to skate well on them. Since our office is with moments, let us husband them…Let us be posed, and wise, and our own, today. Let us treat the men and women well; treat them as if they were real; perhaps they are….I know that the world I converse with in the city and in the farms, is not the world I think. I observe that difference, and shall observe it. One day I shall know the value and law of this discrepancy. But I have not found that much was gained by manipular attempts to realize the world of thought. Many eager persons successively make an experiment in this way, and make themselves ridiculous.