Background

Although Washington Square was well received and beloved by his contemporary readers and beyond, Henry James disliked it. In fact, he was unable to reread it, causing Washington Square to not be included in the New York Edition of his fiction.

James had multiple sources for the novel’s plot. The most famous source is actress Fanny Kemble, who was known for her massive supply of gossip. According to the Oxford World Classics edition introduction, written by Adrian Poole, Henry James wrote down the details of a story she told him in his diary. This story shares the main four characters and the basic plot of what eventually would become Washington Square. More importantly for my interests, James also pulled from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Rapacinni’s Daughter,” which also features an imprisoned, innocent daughter, a tyrannical father, and a young male lover who appears to promise liberation.

Plot Summary

The novel is told from a third-person omniscient point of view. The narrator often offers his comments directly to the reader (“though it is an awkward confession to make about one’s heroine, I must add she was something of a glutton”, Chapter II)

The novella begins at a distance from the characters, describing the background of the Sloper family. It then recounts in detail the story of Catherine’s romance with Morris Townsend. When Morris jilts her, the focus shifts back to a long view. As James puts it: “Our story has hitherto moved with very short steps, but as it approaches its termination it must take a long stride.” The final few chapters are taken once more in short steps, ending with the striking vignette of Catherine’s refusal of Morris. 1

Notes & Quotes

- Washington Square provides me with yet another iteration of the marriage plot in 19th century American literature. I’m interested in the ways that James subverts the seduction narrative. In early American fiction, women who failed to obey or to share everything related to their courtship and intended with their parents often met tragical ends. Catherine is extremely honest with her father, however, she decides to go against his wishes and engage herself to Morris. Additionally, the reader is made to judge the father as cruel and cold-hearted. This makes it difficult for even the reader to decide what Catherine should do, or who she should trust. It really displays the need for young women to have reasonable and moral support systems- Mrs. Penniman is not reasonable and is selfish, while Dr. Sloper is too reasonable and cruel towards his own daughter. Catherine longs for a female companion and, while in Europe, she almost shares her thoughts to working-class women.

- Again, like the other marriage and seduction narratives on this list, the language of gambling and financial value dominate the narration. I am particularly interested in Dr. Sloper’s observation that Catherine’s value increases after he had taken her on a tour of Europe: “I have done a mighty good thing for him in taking you abroad; your value is twice as great, with all the knowledge and taste that you have acquired” (117). Catherine is thereby viewed as an entrepreneur of the self, she has increased the value of herself as commodity.

- There is also an extreme value placed on sight and performance. Morris is very enamored with “natural” qualities, however, he is also the most skilled performer (and therefor is unnatural) in the novel. It’s difficult for the narrator to pin a single version of Morris down, and we are instead shown the noble lover, the petulant son, the self-indulgent idler, etc. Strangely, after the dissolution of her engagement, Catherine is not removed from the visible network of NY society (as the fallen and broken-hearted women in other seduction novels on this list do), and instead becomes even more visible after her removal from the market.

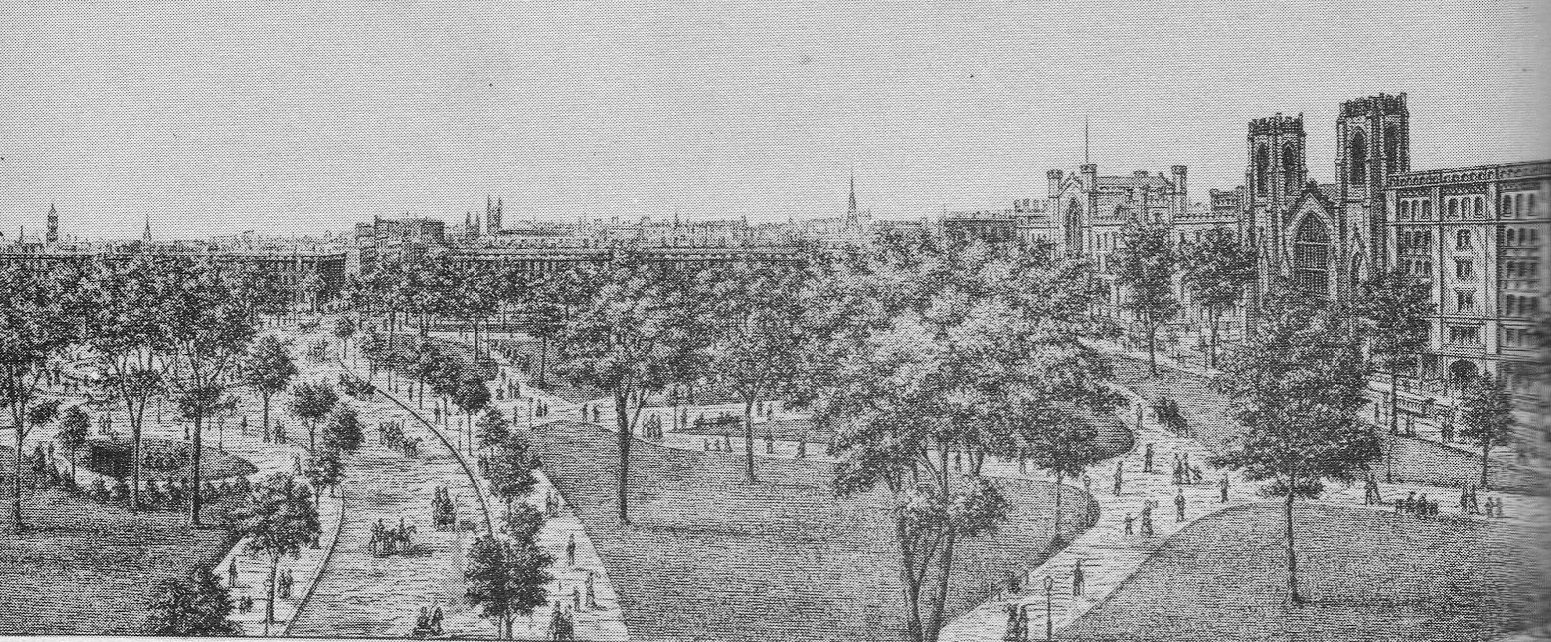

- The selection of Washington Square as the site of most of the drama, as well as the title, is important. As Adrian Poole notes, it was originally a potter’s field with a public gallows at the end of the 18th century, then at the start of the 19th century, Washington Square was a burial ground for the poor. Finally, in the late 1820s and 1830s, it was developed into a housing ground for the middle and upper classes (xv). This provides a classically gothic location for James’s novel, a sort of haunted ground that threatens a return of the past. Similarly, Catherine is haunted by the memory of her mother (whom she is named after) who outshines her in every way and whose former glory prevents Dr. Sloper from truly loving Catherine. Additionally, Poole notes that James viewed Catherine as an innocent American (pre-Civil War) who appears to have nothing to write about (James viewed the American of Hawthorne’s era to be empty of the traditions, customs, and culture that British and European easily wrote of).