Background

“Rip Van Winkle” was one of the first stories that Washington Irving wrote as part of his 1819 collection, The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Although Irving was an American and the collection is certainly an example of American literature, Irving wrote it while living in Birmingham, England after he and his brothers suffered major financial losses as a result of the War of 1812. One of the larger purposes of this text was to separate American from British culture as something worthy in its own right, as well as to begin the process of creating an American culture. The collection is a frame narrative, written largely by the fictional Geoffrey Crayon, who inserts stories by the equally fictitious Diedrich Knickerbocker into his “sketchbook.” “Rip Van Winkle” is one of the stories attributed to Knickerbocker.

Plot Summary

The story opens with Crayon’s claim that the following story came from the papers of Diedrich Knickerbocker, a man who was very knowledgeable in the early Dutch history of New York despite the fact that he preferred to consult a “genuine Dutch family” as opposed to printed history. The story focuses on Rip Van Winkle, a henpecked husband of a demanding woman, Dame Van Winkle, a father of two, and a favorite among the children of the neighborhood. Van Winkle is very helpful and accommodating to his neighbors, always happy to assist on their farms or in their errands, however, he hates to do his own labor, so his farm is quite deteriorated and small. As the story states, “Rip was ready to attend to anybody’s business but his own…” Frustrated in his failure to perform neither his domestic nor agricultural duties, Rip’s wife often turned him out of the house. On these occasions, he would head to the local inn where he would converse with a familiar group of men, or he would take his dog Wolf and his gun to the woods of the Catskill Mountains to partaking in walks and squirrel-hunting. During one of these trips, Rip ran into a group of strange looking, short, squat, serious men, dressed in old, “quaint outlandish fashion.” They play “nine pins” and drink from a large keg, which is offered to Rip, who greedily and repeatedly drinks the drought. When he wakes up, he finds himself still on the Catskills, however he quickly notices a number of changes: his new gun has been replaced with a rusty one and his dog is missing. He walks back to town, nervous to face Dame Van Winkle’s reaction to his spending the night in the woods. Rip is surprised when he finds that he can’t recognize anyone he passes in town, and remarks upon the looks of confusion repeatedly aimed at him. He puts his hand to his chin and realizes that he has grown a foot-long beard. He arrives at the inn, which used to have a portrait of King George III, but this has been painted over to look like George Washington. A man asks Rip how he plans to vote for congress: republican or democrat. Rip cannot understand what he is asked and tells the people that he is a simple subject of the king, who means nobody any harm. The locals grow angry, but he eventually asks, after learning that most of his inn-friends are dead and that a war had recently occurred, if anybody knows Rip Van Winkle. The townspeople point out an idle and wild looking man, the exact replica of Rip himself. This initially bewilders Rip, but he soon learns that this is his grown-up son. Rip’s daughter, now a mother, approaches him and asks if he is her father. Rip asks whether Dame Van Winkle is dead. After his daughter answers in the affirmative, Rip admits that he is her father. He learns that he had been missing for the last twenty years, and that the locals assumed that he was either killed by Indians or shot himself. Peter Vanderdonk, the son of a local historian, credits Rip’s story, claiming that he knew and heard of the beings who haunt the Catskills: “That it was affirmed that the great Hendrick Hudson, the first discoverer of the river and country, kept a kind of vigil there every twenty years, with his crew of the Half-moon; being permitted in this way to revisit the scenes of his enterprise, and keep a guardian eye upon the river and the great city called by his name.” Rip, given his old age, becomes a venerated figure and artifact of the times before the war. Many are happy to hear him tell his tales as he sits by the inn. The story closes with a few post-scripts from the notes of Knickerbocker claiming that, despite the story’s similarities to a German myth, he knows them to be completely true and completely American.

Notes & Quotes

- Irving makes a point to ensure that, although he pulls from German legend, his tale is deeply American. He first does this by situating it in the Catskills of New York, and near the end of the story, the supernatural beings are described as being under the leadership of the spirit of Henry Hudson. Additionally, the American landscape is connected to the supernatural elements in the story. It is while he is deep within the Catskills, which the narrator claims has always been imbued with legend:

The Kaatsberg or Catskill mountains have always been a region full of fable. The Indians considered them the abode of spirits, who influenced the weather, spreading sunshine or clouds over the landscape, and sending good or bad hunting seasons. They were ruled by an old squaw spirit, said to be their mother. She dwelt on the highest peak of the Catskills, and had charge of the doors of day and night to open and shut them at the proper hour. She hung up the new moons in the skies, and cut up the old ones into stars. In times of drought, if properly propitiated, she would spin light summer clouds out of cobwebs and morning dew, and send them off from the crest of the mountain, flake after flake, like flakes of carded cotton, to float in the air; until, dissolved by the heat of the sun, they would fall in gentle showers, causing the grass to spring, the fruits to ripen, and the corn to grow an inch an hour. If displeased, however, she would brew up clouds black as ink, sitting in the midst of them like a bottle-bellied spider in the midst of its web; and when these clouds broke, woe betide the valleys!

It’s important to note here, too, that American nature and elements of the supernatural are tied to the American Indian. This further adds to the American authenticity of “Rip Van Winkle” and to the American culture with Irving hoped to create. Additionally, the “wild” aspect of the area where Rip ventured is repeated multiple times throughout the story. Even before his sojourn into the Catskills, Rip is surrounded and defined by wildness: his children are described as “wild and ragged” and his farm is not maintained; He is forced by his wife to “take to the outside of the house—the only side which, in truth, belongs to a henpecked husband” and his sole companion is his dog named Wolf. However, unlike the characters of American ecogothic narratives, Rip does not become “bewildered” (Irving uses this word) until he returns to town and hears talk of voting and war.

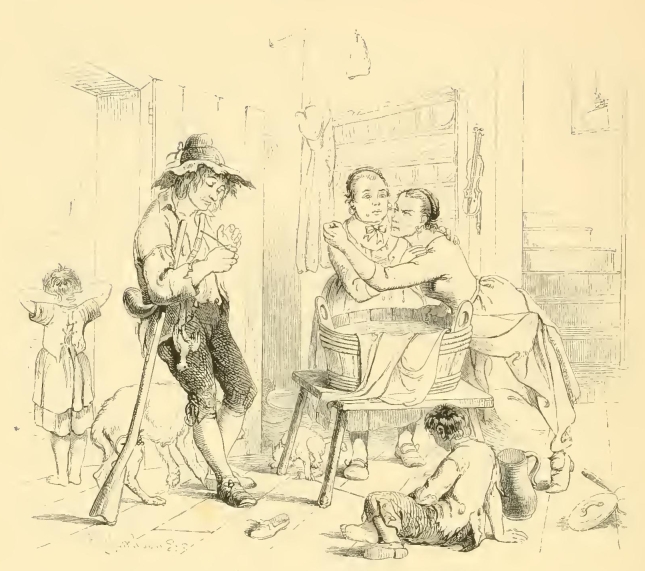

Rip is wild-looking even before he grows his foot-long beard.

- The role of the story teller in American society is important to “Rip Van Winkle.” Right from the start of the story, the narrator tells the reader that Knickerbocker viewed people as more trustworthy and authentic sources of American history as opposed to books and the written word. According to this logic, the authentic America is found in its nature and in its people and cannot be written down. So, can Irving create American literature? Is this even possible? Is this why he takes the form of a storyteller and focuses so much on legends and the discovery of Knickerbocker’s papers?