Background

Hard Times is the shortest of Dickens’s novels and, unlike his other novels, contains no illustrations and has no preface. It has no scenes in London, but instead takes place in the fictional Coketown, a mill-town somewhere in Northern England.

According to its Wikipedia page, Hard Times was written at least partly because of the low sales of Dickens’s weekly periodical, Household Words. He believed that publishing a new novel would boost circulation of the periodical, which is exactly what wound up happening.

Upon its publication (and since), Hard Times received mixed critical reviews. John Ruskin claimed that Hard Times was his favorite Dickens novel; Thomas Macaulay viewed it as “sullen socialism”; George Bernard Shaw stated that, although it was a “passionate revolt against the whole industrial order of the modern world,” it failed to give a realistic account of trade unions.

Plot Summary

The story follows the rise of Gradgrind’s two children, Tom and Louisa (“Loo”), who were raised to trust and indulge only in facts and rationality, never in feelings or fancy. Because of Gradgrind’s connection as superintendent to the local school, he meets Cecilia “Sissy” Jupe, who is not a great student despite the fact that she tries, and is the daughter of a horse-breaker from a traveling circus. When her father disappears, Gradgrind offers to take her in as a means to prove that his system of facts could reform Sissy, so long as she agreed to never speak to or see the circus people ever again. Gradgrind’s associate, Josiah Bounderby, is a “self-made” man who has risen to a position of power from his humble origins. He controls the bank and employs many of the mill-workers. Bounderby employs Mrs. Sparsit, a high-born widow who lost her fortune due to her gambling husband. She is a figure of pride to Bounderby. Louisa marries Bounderby despite their considerable age gap and the fact that neither of them love each other. It was her education in pure fact that at least partly causes her acceptance of the marriage. Tom falls into bad gambling habits after he meets James Harthouse, a gentleman who arrives to Coketown with a letter of recommendation to Bounderby after several occupations bored him. Harthouse also seeks to woo Louisa, but after failing to do this, he leaves. Mrs. Sparsit discovers what she believes to be a secret affair between Louisa and Harthouse, and tells Bounderby. Bounderby refuses to take Louisa back into his home, she happily returns to her childhood home when her father apologizes to her for bringing her up to only believe in facts. Tom takes on gambling debts, but Louisa refuses to give him any more money. Tom, Louisa, and Sissy meet Stephen Blackpool, a weaver and employee of Bounderby, who has been ostracized by the community of laborers after he refused to join their union. They also meet Rachel, Blackpool’s love interest, and a strange old lady known as Mrs. Pegler, who is later revealed to be Mr. Bounderby’s mother. Blackpool must leave Coketown in order find a job elsewhere. Tom privately asks him to stand outside of Bounderby’s bank at night in exchange for some money. It is through this odd request that Blackpool becomes framed for a bank robbery which Tom commits. After Blackpool leaves, Bounderby posts wanted ads with a considerable reward for Blackpool’s discovery and apprehension. Rachel sends a letter to Blackpool asking him to come back in order to prove his innocence. When he doesn’t return, Rachel gets nervous and other characters begin to suspect his guilt. While on a walk outside of Coketown, Rachel and Sissy discover Blackpool’s body at the bottom of an abandoned pit shaft. Blackpool is barely alive, but it is enough to prove his innocence and Tom’s guilt. Tom tries to run away, and Gradgrind tries to help his son. Tom goes under disguise with the circus people, and is eventually able to escape.

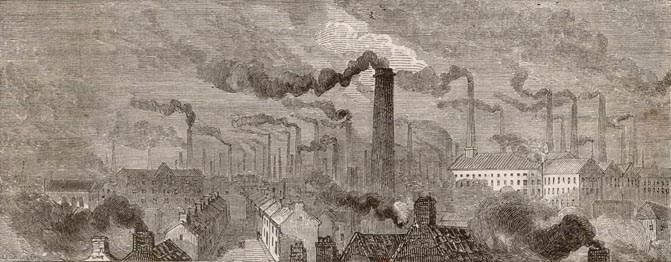

A view of the factories of Manchester. Date: circa 1870 Source: Unattributed illustration.

Notes & Quotes

- I was fascinated by the urban landscape of Coketown presented in Hard Times. The constant streams of smoke, as well as the black cloud that hangs over Coketown are particularly interesting. The land surrounding Coketown is made all the more dangerous due to the coal mining work that had once occurred there. Blackpool falls down and dies in an abandoned shaft. The fact that this shaft was abandoned makes it all the more gothic: it is a sort of a return of the repressed. Additionally, this fits well with the ecogothic. Human interaction with the environment (the coal mines and the mills) has changed nature for the worse. Just like Gradgrind attempted to raise his children rationally, completely denying them a sentimental education, the transformation of nature by industrialism is completely reliant on rationality and efficiency, however, it destroys the human body along with the environment.

It was a town of red brick, or of rich that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal in it, and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next. (16)

In the hardest working part of Coketown; in the innermost fortifications of that ugly citadel, where Nature was as strongly bricked out as killing airs and gases were bricked in; at the heart of the labyrinth of narrow courts upon courts, and close streets upon streets, which had come into existence piecemeal, every piece in a violent hurry for some one man’s purpose and the whole an unnatural family, shouldering, and trampling, and pressing one another to death; in the last close nook of this great exhausted receiver, where the chimneys, for want of air to make a draught, were built in an immense variety of stunted and crooked shapes, as though every house put out a sign of the kind of people who might be expected to be born in it: among the multitude of Coketown, generically called “the Hands,”- a race who would have found more favor with some people, if Providence had seen fit to make them only hands, or, like the lower creatures of the seashore, only hands and stomachs- lived a certain Stephen Blackpool, forty years of age. (47)

..before pale morning showed the monstrous serpents of smoke trailing themselves over Coketown. A clattering of clogs upon the pavement; a rapid ringing of bells; and all the melancholy mad elephants, polished and oiled up for the day’s monotony, were at their heavy exercise again. (51)

Stephen Blackpool: “…I ha’ read on ‘t in the public petition, as only one may read, fro’ the men that works in pits, in which they ha’ pray’n and pray’n the lawmakers for Christ’s sake not to let their work be murder to ’em, but to spare ’em for th’ wives and children that they loves as well as gentlefok loves theirs. When it were in work, it killed wi’out need. See how we die an’ no need, one way an’ another- in a muddle- every day!” (204)

- The character of Mr. Bounderby is vital to Dickens’s representation of capitalism. He is the “self-made man” who repeatedly looks down on his “Hands” and on his own mother. He collects high-born friends (the Gradgrinds and Harthouse), a high-born wife (Louisa) and a high-born employee (Mrs. Sparsit). By placing these objects of position near his own body, his own value becomes increased (at least in his perspective). He constantly boasts of his own ability to create his own fortune and his status of “self-made.” I think this could be a great text to teach in our current age of neoliberalism because of the “self made” rhetoric that permeates our own culture, as well as the belief that the poor simply are too lazy and/or untalented to turn themselves into “self made” individuals. This rhetoric, along with Bounderby’s, works to obscure the luck and other public systems (racism, sexism, etc) that allow for the success of some, and instead turns it into a private matter- that Bounderby is hard-working, while Rachel and Stephen Blackpool are not.

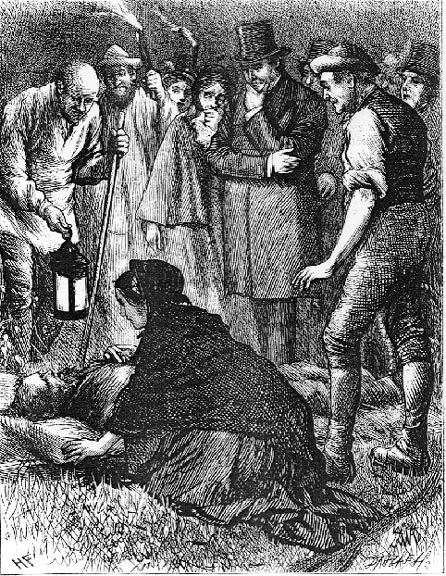

Rachel and Bounderby, Harry French – Illustration for Dickens’s Hard Times for These Times in the British Household Edition

- Finally, I think this novel would serve as a great primary source for a study on conceptions of the mind and body in the 19th century and/or affect theory. Gradgrind’s and Bounderby’s obsessive focus on the mind causes them (and Louisa and Tom) to experience various forms of degradation. Through this novel, Dickens instead argues for an education or philosophy that encourages the development of both mind and body, the body being the site of feeling, imagination, and sentimentality. This connects to the larger representation of Coketown’s landscape. The town’s “mind” worked efficiently (the factories produced capital), but its body was destroyed (smoke, etc.).