I recently read Sara L. Crosby’s article, “Beyond Ecophilia: Edgar Allan Poe and the American Tradition of Ecohorror” and immediately wanted to try to apply Poe’s “third model” for human interaction with the environment to another text. 1 This week, in my “American Gothic” independent study, I’m reading a number of  Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short stories alongside a number of Poe’s. As it prominently features a terrifying walk through the American wilderness, I thought it might be interesting to apply Crosby’s ideas to Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown.” 2

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short stories alongside a number of Poe’s. As it prominently features a terrifying walk through the American wilderness, I thought it might be interesting to apply Crosby’s ideas to Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown.” 2

Spoiler alert: Goodman Brown is an awful eco-detective.

Sara L. Crosby and the Third Model of Human/Environment Interaction

Crosby opens up her article by describing the two common models of interacting with the environment as presented in American culture. The first she describes as “ecohorror,” a very popular mode of representing environmental issues today. Consider the seemingly  endless list of apocalyptic films in which environmental catastrophe wreaks havoc on humanity. She provides Simon Estok’s definition of ecohorror: “…the irrational and groundless hatred of the natural world.” 3 The second American mode of responding to the environment is known as “ecophilia,” or the love of nature. Crosby notes that this sort of response to nature can be just as potentially dangerous as ecohorror. This sort of love is typically the bad kind, which presupposes that the earth is a mere extension of humanity, provided to mankind simply for our pleasure and self-exploration.4

endless list of apocalyptic films in which environmental catastrophe wreaks havoc on humanity. She provides Simon Estok’s definition of ecohorror: “…the irrational and groundless hatred of the natural world.” 3 The second American mode of responding to the environment is known as “ecophilia,” or the love of nature. Crosby notes that this sort of response to nature can be just as potentially dangerous as ecohorror. This sort of love is typically the bad kind, which presupposes that the earth is a mere extension of humanity, provided to mankind simply for our pleasure and self-exploration.4

Thankfully, Crosby offers us an alternative narrative mode that is both proactive and found in American literature via Edgar Allan Poe’s “ecological detective” figure. 5 The successful ecological detective is exceptionally presented through Legrand in “The Gold Bug” and engages in the “surface reading” of the environment in order to discover and interpret “human traces” on the earth’s landscape. 6. Poe does “other” the environment, however, Crosby argues that he does this out of “respect” to the earth, as well as to make “an indictment of the human ego.” 7 Poe scoffed at what he viewed as the arrogance in believing that man can know and learn all. He attributed this sort of arrogance to any who believed that mankind was “of more moment in the universe than that vast ‘clod of valley’ which he tills and contemns, and to which he denies a soul for no more profound reason than that he does not behold it in operation.” 8 Through the ratiocinative method exhibited by his detectives, Poe promotes a way of interacting with the environment that encourages the surface reading of human traces on the earth, rather than destructive and violent intrusion. According to Crosby, this sort of interaction encourages neither the fear nor the love of nature (she argues that American culture is not quite ready for the “good” sort of love of the earth), but rather pushes for a rational, nonviolent and respectful approach.

“Young Goodman Brown”

So what happens when we interpret Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” via Poe’s ecological detective?

The environment, as portrayed in “YGB,” is pure ecohorror and clearly finds its roots in  the Puritan tradition. Through this point of view, the American landscape is viewed as a fallen, cursed, earth, directly connected to the Biblical story of the Fall of Man. 9 The American wilderness was something to be both feared and deeply read. Both God and the devil were believed to be able to “regularly intervene” with mankind, often through the Earth.10 For all of these reasons, the dangerous acquisition of knowledge is often tied to the unruly landscape in American gothic texts.

the Puritan tradition. Through this point of view, the American landscape is viewed as a fallen, cursed, earth, directly connected to the Biblical story of the Fall of Man. 9 The American wilderness was something to be both feared and deeply read. Both God and the devil were believed to be able to “regularly intervene” with mankind, often through the Earth.10 For all of these reasons, the dangerous acquisition of knowledge is often tied to the unruly landscape in American gothic texts.

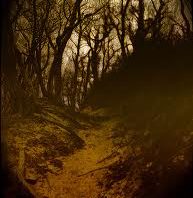

As Goodman Brown delves deeper into the woods near his Salem community on the Walpurgisnacht, 11 the narrative describes the haunted aspect of the wilderness: odd voices seem to travel on the wind, while hidden creatures possibly watch Goodman Brown behind the obscurity of the forest. Emphasizing the haunted forest’s relationship to the Fall of Man even further, Goodman Brown’s ominous guide through the forest brandishes a serpent-like staff as he leads Brown deeper into the woods.

Hubert Zapf argues that Hawthorne incorporates two versions of the Faustian myth into “YGB”: the Puritan warning against the pursuit of knowledge and sin, and Goethe’s rendition which presents a sympathetic Faust who performs transgressions only so that he may improve mankind. 12 In Brown’s quest for knowledge and/or sin, he deeply penetrates the wilderness and rapidly looses himself to pure ecophobic observations regarding the forest. He imagines that nature itself laughs at him and “roars” in support of the devil. 13 While he is sometimes able to notice human traces within nature (the sounds of the satanic group’s chanting, the group’s blazing torches, etc), he primarily views the environment as one oppositional to humanity and goodness, as well as one that is able to mimic human invention (“…a rock, bearing some rude, natural resemblance either to an altar or a pulpit…” (175).

Goodman Brown’s quest into the wilderness is the exact sort which, according to Crosby, Poe opposed. In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Crosby reads a critique of an ecophobic and “hubristic reading of nature” which assumes that nature is evil, antagonist to humanity, and therefore should be conquered by the civilizational processes of man. 14 Not only does Goodman Brown ascribe to the same beliefs held by Roderick Usher and the narrator of “Usher,” but Brown exhibits the destructive and obsessive thirst for knowledge and sin connected to the Puritanical version of the Faust myth. 15 Although Brown tries to correctly read and interpret the haunted forest, he employs a Puritan typology rather than the surface-level ratiocinative method which Crosby recommends. Seen in this way, Good Brown becomes a misguided eco-detective.

Hawthorne does provide one character who exhibits some characteristics of the successful eco-detective. Faith, Goodman Brown’s new wife, is able to see the dark ecology of the haunted forest and her community, and live with this knowledge. Unlike her husband, Faith does not transform into a joyless, cold shell after confronting this sinful wilderness. Rather than succumbing fully to ecophobia (or ecophilia), Faith acknowledges her fears but is ultimately able to move past them: “A lone woman is troubled with such dreams and such thoughts that she’s afeard of herself sometimes” (169, emphasis added). Zapf notes Faith’s “joyful acceptance of the natural forces of life,” 16 seen most clearly when she allows “the wind play with the pink ribbons of her cap” near the start of Hawthorne’s story (169). Her emotional life is not tainted by her experience with nature, nor does she hubristically view nature as an extension of herself. While she may appear only minimally in “YGB,” Faith seems to provide the same alternative to the false choice between ecophobia/ecophilia within American literature as does Poe’s eco-detective.

- Crosby, Sara L. “Beyond Ecophilia: Edgar Allan Poe and the American Tradition of Ecohorror.” ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 21, no. 1, 2014, pp. 513-525. ↩

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel. “Young Goodman Brown.” The Scarlet Letter and Other Writings, edited by Leland S. Person, Norton Critical Edition, 2017, pp. 169-178. ↩

- Crosby, 514. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 515. ↩

- Ibid., 522 ↩

- Ibid., 518 ↩

- Poe, quoted in Crosby, 518. ↩

- Hillard, Tom J. “From Salem Witch to Blair Witch: The Puritan Influence on American Gothic Nature.” Ecogothic, edited by Andrew Smith and William Hughes, Manchester University Press, 2013, pp. 110. ↩

- Ibid., 107 ↩

- According to Hubert Zapf, the Walpurgisnacht is, according to German legend, the “one special night in the year, the summer solstice, in which ghosts and spirits are said to be abroad, and in which the witches travel on broomsticks to Blocksberg Mountain where they gather to meet their master, the devil, and to celebrate orgiastic feasts” (29). ↩

- Zapf, Hubert. “The Rewriting of the Faust Myth in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘Young Goodman Brown,'” Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, vol. 38, no. 1, 2012, pp. 19-40. ↩

- Hawthorne, pp. 174, 177. ↩

- Crosby, 519-520. ↩

- Zapf, 20. ↩

- Zapf, 35 ↩

There’s a danger of imposing too much modern thinking on Hawthorne’s characters, I suppose. Faith’s joyful acceptance of the forces of nature tempts me to ascribe feminist impulses to Hawthorne that might not be real–say that the woods inhabited by supernatural demonic forces is all a result of not embracing “nature” enough, ie, be like Faith. Yet the fact of Faith’s existence in the story allows it to court such modern/postmodern/feminist interpretations over the passage of time, which is pretty awesome, and is one of the reasons the story continues to be relevant.

Thanks for your response, Professor Davidson!

Yes- I completely agree with you regarding the dangers of too freely reading Hawthorne under a contemporary lens. As I begin to gain more interest in the ecogothic (a very new school of thought, branching off from ecocriticism), I need to remind myself to tread lightly while applying it to older texts.

Faith is a great character for interpretation. Your reading of Faith’s relationship to nature as potentially feminist is particularly exciting because, by the end of the story, she is viewed by Goodman Brown as something close to a witch. Of course, attaching feminism to witchcraft (and nature) would be extremely anachronistic if applied to a Hawthorne text like this one.