Female and POC wrestling fans often find themselves in the bizarre (yet common to many fandoms) position of simultaneously being both outsiders and insiders of the community. We learn the lingo, the characters, and the history, yet we are often policed by (white) male fans and disappointed by misogynistic storylines (an example), racist storylines, and the McMahon family’s connection to Donald Trump. For better or worse, most of these issues are becoming less overt due partly to the brand’s move to ‘PG’ programming. We are currently witnessing what has been titled the “Woman’s Revolution” of pro-wrestling, ushered in by the “Four Horsewomen” (from left to right in the image below) Becky Lynch, Bayley, Charlotte Flair, and Sasha Banks (however, I’d argue that the origins of the Women’s Wrestling Revolution can be traced earlier to wrestlers like Chyna, Lita, and others and I’m sure the Four Horsewomen would agree).

With the “Women’s Revolution,” wrestling fans have been treated to women’s matches lasting more than five minutes (gasp!), fully fleshed out female characters who are not always connected to male counterparts, and a number of firsts, including the first ever Women’s Money in the Bank Ladder Match (largely a disappointment) last year and the first Women’s Royal Rumble Match last month (not a disappointment at all). The women’s wrestling division has moved away from the “Bra and Panty” matches into new territory, where the focus is more on the women’s athletic skill and character archs.

For this week’s blog post, I’d like to examine the role that the Internet has played in the development of the WWE Women’s Revolution. I will first explore WWE’s digital actions before diving into the unofficial moves enacted by fans and the female wrestlers online. I will keep in mind Jessie Daniels’s important point that companies have often “co-opted the rhetoric of feminism for profit.” 1 Unfortunately, the WWE is extremely guilty of this, however, as I have discovered through crafting this blog post and via my own involvement, the female fandom and wrestlers seem to genuinely enact methods of cyberfeminism(s) through their interactions online.

Mixed-Match Challenges and Feminist Heels

Stephanie McMahon, daughter of Vince McMahon, is the current Chief Brand Officer of  the WWE, as well as the on-screen commissioner of Raw (WWE’s Monday night programming). As one of the faces of the business, her on-screen character “Stephanie McMahon” is a heel (wrestling term for villain) who is largely hated by fans. However, her role is also colored by her support for women’s wrestling and her push towards digitizing the company. A few months after her call for a women’s revolution in wrestling, the Diva’s Butterfly Champion Belt was terminated in favor of a Woman’s Championship Belt.

the WWE, as well as the on-screen commissioner of Raw (WWE’s Monday night programming). As one of the faces of the business, her on-screen character “Stephanie McMahon” is a heel (wrestling term for villain) who is largely hated by fans. However, her role is also colored by her support for women’s wrestling and her push towards digitizing the company. A few months after her call for a women’s revolution in wrestling, the Diva’s Butterfly Champion Belt was terminated in favor of a Woman’s Championship Belt.

Yep, three years ago, women’s wrestling had the Diva Belt.

Stephanie also pushed for all pay-per-view shows to no longer be aired via the pay-per-view system. Fans now can pay the monthly price to view all of the major matches through the WWE digital streaming service. This change occurred around the same time as the change of the women’s belt.

The digitalization of WWE matches has recently reached an extreme through the WWE Mixed-Match Challenges which are currently airing on Facebook every Tuesday night after Smackdown (around 11 pm). Although they are not exactly intergender wrestling (two genders wrestling each other), they feature fights between tag-teams composed of one female and one male wrestler. Fans vote online to create their dream teams and are able to comment throughout the matches in a live discussion thread (Interested in watching one? Example 1. Example 2.).

In her Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway defines the cyborg as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” (149). The world of wrestling constantly toys with the creation, replacement, and, to borrow Haraway’s term, “regeneration” of identities (181). Just as it was difficult for me to explain the differences between the “real” Stephanie McMahon and her WWE persona, so it is for every other character/athlete/entertainer who appears within the ring. Wrestlers can swiftly change characters (Mick Foley’s three appearances within a single Royal Rumble in 1998 is a prime example) and their characters can easily move from heel to face (the term for heroic characters) and back again. Identities here are fluid and ever-changing. By creating a digital side-narrative in which women and men have equal airtime, the WWE has inadvertently come close to this vision of the cyborg. Each team is a chimera of identity (sometimes pairing a heel with a face) and gender. The matches themselves are also “hybrids of machine and organism,” as they are both performed live by physical bodies, yet these bodies are watched by millions of viewers through Facebook’s interface.

I don’t think that members of the WWE marketing team have read the “Cyborg Manifesto” (maybe I’m judging unfairly), however, the cyborg identity is surprisingly prevalent within the digital campaigns promoting the Mixed-Match Challenges. In the midst of these fights, the WWE released a set of promotional images, featuring the mixed-match teams with swapped faces. These digital, monstrous bodies put forth by the WWE are cyborg-esque, as they seem to connect with Haraway’s idea of the “network ideological image” which allows for permeable body boundaries. These digitally-constructed bodies also provide a great visual representation of what Sherry Turkle describes as the loosened repressive boundaries resulting from “assuming alternate identities online” (cited in Daniels 110). Through these assumed digital identities, gender can be transformed, manipulated, made monstrous, and/or even disposed.

The image at the top of my blog post features Alexa Bliss, a heel within the women’s wrestling division. This image was one of the first used to promote the Mixed-Match Challenge. Alexa’s face becomes the space where Facebook and the WWE can merge, allowing her to take on a cyborg physicality. When I first saw this photo, I became excited: was this signaling that the Facebook challenges would be written and performed through the cyborg female gaze? Unfortunately, based on what I’ve seen of the Mixed Matches, this doesn’t seem to be the case.

By the way- Alexa is becoming another feminist heel. She’s been villainous for most of her career (I’m still relatively new to the fandom, so she may have ALWAYS been a heel, but I’m not sure), but she recently cut a promo in which she demanded more gender equality from the (male) general manager, Kurt Angle. It’s difficult to tell whether or not the mainly male audience is cheering her on, but the segment ends with her disappointment. This occurred earlier this month, and nothing has yet furthered this plot-line (ie: her sudden feminism, not the storyline surrounding the Championship belt), so it’s difficult to say what the WWE writers were going for here. Either this was an aspect of her heel-identity or they are preparing her for a face turn. No matter what, you can check out the comments of the Youtube video to see how her anger and frustration is sexualized by some fans while others complain about “SJWs” like Alexa are infiltrating their beloved fake sport. Yikes.

Cyberfeminisms of the WWE Fandom

This blog post is getting longer than I planned and I need to be finished in time for the WWE PayPerView tonight. I’ll try to make this section brief!

Although the WWE’s attempts towards feminism seem to be mainly mere surface-level displays for capitalistic gain to attract more female viewers, some of the fans and some of the wrestlers have created spaces for cyberfeminist tactics online. Some areas of the internet, like the “SquaredCircle” subReddit are a bit nasty, while spaces like Wrestling!Twitter can be truly wonderful places to network, share, complain, celebrate and discuss.

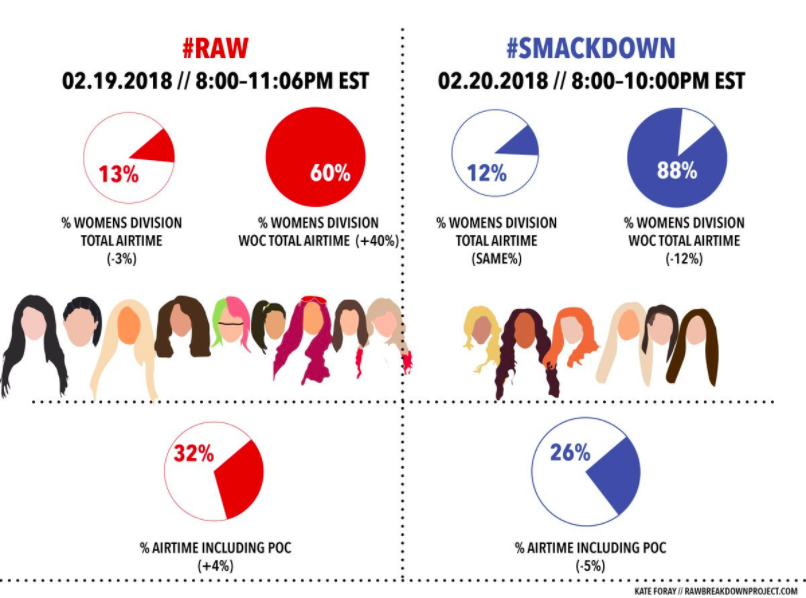

Kate, AKA @makeitloud on Twitter, is a graphic designer and “wrestling aficionado” according to her profile bio. Every week, she shares her graphic depictions of women and POC air-time on Raw and Smackdown to raise awareness of gender and racial inequality in wrestling. Here is last week:

By creating graphic depictions of WWE airtime for both women and POC, Kate is working within a cyberfeminism that is neither a monolithic theory nor part of the overwhelmingly white “old” feminism discussed by Jesse Daniels (102).

Besides discussing wrestling and sharing fan-created work, Twitter is also used by the fandom to create change. As described in this NPR article, the immense use of #GiveDivasAChance on Twitter was part of a larger social media movement which helped lead to the so-called Women’s Revolution in wrestling. These fans were aware of the company’s desire to attract fans and deliver matches that would bring in more capital, and made use of Internet spaces to incite change.

Female wrestlers also use Twitter for cyberfeminist means, however, it is once again difficult to discern whether or not these are moves by the actual human beings themselves or by their character as written by the WWE. Maybe this is a weird version of Poe’s Law?  Wrestler Nia Jax took to Twitter recently to speak against body shaming, while many women’s wrestlers, like Charlotte Flair, have used Twitter as a platform to situate their matches within the Women’s Revolution narrative and to support other female wrestlers. This demonstrates a use of social media as a digital extension of their (real?)(performed?) identities in order to “be protagonists in their own revolution” (Daniels 118). Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts maintained by wrestlers are fascinating to examine under this cyberfeminist lens. They seem to not only assist in the creation of community spaces, large-scale representation, and empowering narratives, but they also assist in the transmedia creation of wrestling identities. As each wrestler is spread across the digital and physical realms, their multiple selves and personas allow for a helpful reading of the cyborg figure.

Wrestler Nia Jax took to Twitter recently to speak against body shaming, while many women’s wrestlers, like Charlotte Flair, have used Twitter as a platform to situate their matches within the Women’s Revolution narrative and to support other female wrestlers. This demonstrates a use of social media as a digital extension of their (real?)(performed?) identities in order to “be protagonists in their own revolution” (Daniels 118). Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts maintained by wrestlers are fascinating to examine under this cyberfeminist lens. They seem to not only assist in the creation of community spaces, large-scale representation, and empowering narratives, but they also assist in the transmedia creation of wrestling identities. As each wrestler is spread across the digital and physical realms, their multiple selves and personas allow for a helpful reading of the cyborg figure.

Women’s representation in wrestling still has a long way to go, however, the Internet seems to provide fans and wrestlers alike a platform to demand further improvement. Although the WWE still has a lot of issues, the women’s division has made a lot of progress and features a number of female athletes/performers worthy of being role models to future generations. I feel hopeful.

Questions:

- Can we still celebrate feminist rhetoric when used by massive (problematic) corporations like the WWE? Is it still helpful when they co-opt feminist and cyberfeminist tactics?

- Are female wrestlers online able to engage in cyberfeminism online or are they too attached to the WWE brand and their in-ring identities? Does Poe’s Law come into play here? Are multiple identities conducive to a cyborg identity?

- Jessie Daniels, “Rethinking Cyberfeminism(s): Race, Gender, and Embodiment,” WSQ, 37.1&2, pg. 103. ↩

Interesting post Caitlin. Thanks for the education on the alternate meanings of heels and faces! To your second question: it’s great that you brought up the point about Poe’s Law. I think that similarly to most employees, female wrestlers have to control their public images, especially in regard to how they talk about their employer/terms of employment, whether online or not. Because they are in a field that makes its money from physical and verbal confrontations, it seems very likely that female wrestlers’ cyberfeminism is a managed online confrontation to increase audience interest. Yes, it seems that multiple identities are a necessary part of cyborg identity, which enable successful navigation through differing real-world and online roles and situations.

Thanks for the comment, Vivien! I’m always happy to educate others in all things wrestling.

Yes- the focus on physical/verbal confrontation is definitely part of the issue here. I agree with you- the maintenance of the social media accounts of female wrestlers seem to be controlled at least somewhat by the WWE. I think the transmedia work of the WWE, particularly when it comes to women (not only are there wrestling shows and social media activity, but there is also “Total Divas,” a reality show focusing on a key group of female wrestlers and their day-to-day lives) is sometimes difficult to dissect, especially when trying to find the ‘truth.’ Poe’s Law is handy here, as the wrestling term for ‘in character’ (or fake), “Kayfabe,” is not always sufficient to describing the grey areas of social media.

I agree with Viv that the WWE seems very managed and very much performance-based, although it’s not out of the realm of possibility that a woman could use that performance to forward a feminist agenda. By the way, your blog post was a lot of fun to read and I love how you took us into this field. I would not have thought to look there.

To me, the changing of the belt from the precious Diva Belt to the more mature-sounding Women’s Belt seems like it might have been a genuine feminist impulse on McMahon’s part. That’s just an intuition, since I have no familiarity with her or the WWE. What do you think?

I think that Stephanie McMahon probably is using her position within the WWE to increase women’s representation and to help make the women’s division more honorable. Both McMahon and her husband, Paul Michael Levesque (AKA: “Triple H”) have done a lot of work for women’s wrestling in the past few years that appear to be genuine feminist impulses, as you say. However, I was reminded of Poe’s Law a lot while parsing through WWE politics this week. Since so much operates under kayfabe (in-character), it’s really difficult to definitively say what is real and what isn’t. Maybe most of what is attributed to McMahon regarding her feminist work is actually the work of other members of the company who are more behind-the-scenes. Plus, McMahon’s supposed feminism is often tied to her heel-ness. Over the past two nights, McMahon has appeared on WWE programming with Triple H to welcome Ronda Rousey (yes, Ronda Rousey) to the women’s division of the WWE. McMahon has touted the “fact” that she wanted Rousey to join the WWE but then it was revealed that McMahon is just a corporate villain who just wants to control Rousey and her career (maybe out of jealousy).

McMahon’s ‘character’ behind the scenes as the brand manager for the WWE, however, often works to empower women’s wrestling and to move the WWE into the digital realm. For some reason, these two areas often go hand-in-hand for McMahon.

The post I’ve been waiting for. I may be a convert to the WWE yet; time will tell.

I’m mostly intrigued by this idea of a very constructed character’s feminism. I’m thinking of what you wrote about Alexa, specifically. Her storyline is driven (at least in part) by feminist goals, but are these goals at all productive when viewed in light of the corporation’s high levels of artifice? I’m curious to know. Perhaps the representation of feminism is still useful, but it also gives me pause, thinking about how the WWE seems to be using feminism opportunistically, as a plot-point in a story meant to garner intrigue and more investment from fans.

I can only dream of you converting to the cult of the WWE.

I agree with you- the WWE’s use of feminism feels a bit nefarious, especially given its history as I briefly outlined in my post. Still, it makes me wonder whether or not WWE’s nefariousness even matters so long as their artificial feminism creates some benefits. Certainly, there are a lot more female wrestling fans and there are way more little girls in the crowds looking up to wrestlers like Alexa and others.

I don’t know exactly how it works in the US, but we used to have a really small amateur version of WWE near us (I live in the UK, where WWE isn’t very big at all). It was run out of a nightclub, that they basically converted into a wrestling arena once a week.

In terms of how feminist it was, it depended entirely on the manager at the time, as they wrote the kind of “plot” for the whole thing (plot? I don’t know wrestling terminology, Lol). It started out with a bunch of middle age white men in charge, and they of course made it pretty sexist, where women had no real agency, they either got humiliated by the men or just stood around wearing very little clothing (and pretty much all of the women they hired had huge breasts of course).

Later on though, a woman actually bought the nightclub and took over the whole thing, and she injected it with a heavy dose of feminism. She got more women involved, gave them much better roles, let them choose what to wear, and of course the men got their asses kicked and humiliated a lot more often.

So it was a pretty stark difference between the 2. If you put white men in charge, it’ll just be women lying around with their boobs hanging out. If you put a feminist in charge, it’ll be bad-ass women wearing interesting outfits and kicking all the men in the nuts.

I don’t know how much that helps for the US situation, but I thought it was interesting and worth sharing!

Jane