Background

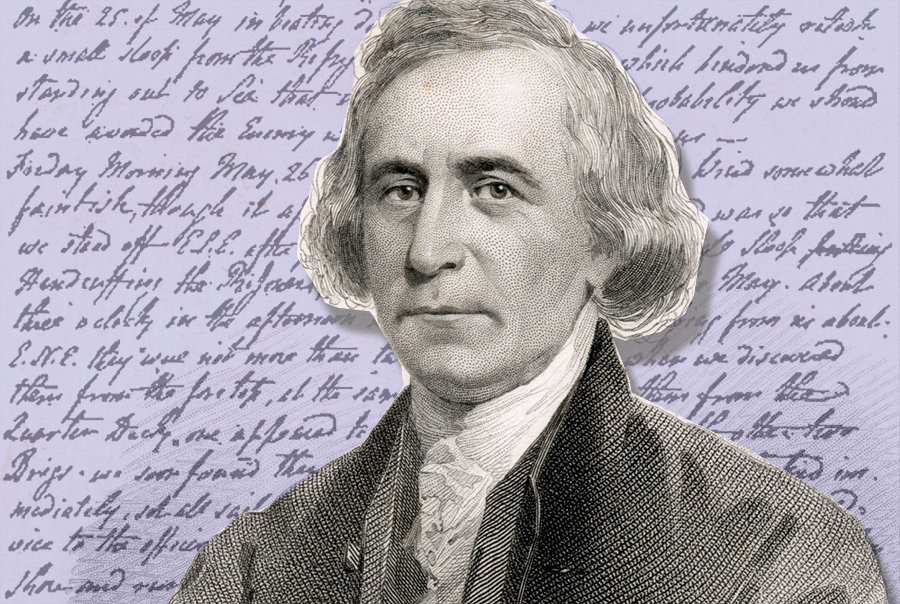

Philip Freneau (1752-1832) was born to a wealthy French family in Manhattan. He worked as a teacher in the United States and later as a plantation secretary in the West Indies in 1776, all while dreaming of becoming a professional writer. It was in St. Croix that he wrote some of his most sensuous and happy poems, however he felt that he could not remain in a land that contained poverty and slavery and write beautiful poetry, causing him to return to the US in 1778 and worked as a seaman on a blockade runner. He was captured at sea and imprisoned on the British ship Scorpion in 1780 and was treated very brutally before his release.

After spending nearly ten additional years at sea, Frenau returned again to the United States, this time to work in the post office in Philadelphia, where he finally would earn his reputation as a journalist, satirist, and poet. He became the editor of Freeman’s Journal and wrote passionately about the American Revolution and became known as the “Poet of the American Revolution.” As secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson hired Freneau as translator in his department, fully aware that Freneau felt strongly in support of the French Revolution. After Jefferson resigned from office and Freneau’s newspaper The National Gazette ceased publication, Freneau earned a living in various ways, from being a ship captain, a newspaper editor, and working on his New Jersey farm, which was slowly sold away. He died impoverished and unknown in the midst of a blizzard.

Poems

“The Indian Burying Ground” (1788)

In spite of all the learn’d have said;

I still my old opinion keep,

The posture, that we give the dead,

Points out the soul’s eternal sleep.

Not so the ancients of these lands —

The Indian, when from life releas’d

Again is seated with his friends,

And shares gain the joyous feast.

His imag’d birds, and painted bowl,

And ven’son, for a journey dress’d,

Bespeak the nature of the soul,

Activity, that knows no rest.

His bow, for action ready bent,

And arrows, with a head of stone,

Can only mean that life is spent,

And not the finer essence gone.

Thou, stranger, that shalt come this way.

No fraud upon the dead commit —

Observe the swelling turf, and say

They do not lie, but here they sit.

Here still lofty rock remains,

On which the curious eye may trace,

(Now wasted, half, by wearing rains)

The fancies of a older race.

Here still an aged elm aspires,

Beneath whose far — projecting shade

(And which the shepherd still admires

The children of the forest play’d!

There oft a restless Indian queen

(Pale Shebah, with her braided hair)

And many a barbarous form is seen

To chide the man that lingers there.

By midnight moons, o’er moistening dews,

In habit for the chase array’d,

The hunter still the deer pursues,

The hunter and the deer, a shade!

And long shall timorous fancy see

The painted chief, and pointed spear,

And reason’s self shall bow the knee

To shadows and delusions here.

In this poem, Freneau is fascinated first by the posture in which American Indians bury their dead- sitting, rather than laying down, as is the Western custom. From this image, he imagines the “restless” spirits of the buried Indians who continue to exist in the American forest, or who are at least fancied to continue living there by the narrator with his “timorous fancy.” Similar to other early American writers of American Indian characters (i.e.: James Fenimore Cooper, Robert Montgomery Bird, etc.), the American Indian is deeply tied to nature. Here, the face of the buried Indian can be slightly seen on a “lofty rock” and each bit of “swelling turf” represents another Indian body. This helps Freneau to participate in romantic primitivism as he views the American Indian as something supernatural and uncorrupted by civilization. He also works to create a historical past for the young nation, placing the American Indian as some sort of past ancestor that is dead and buried, but whose spirit continues to imbue America.

“On Mr. Paine’s Rights of Man” (1791, 1809)

Thus briefly sketch’d the sacred Rights of Man,

How inconsistent with the Royal Plan!

Which for itself exclusive honour craves,

Where some are masters born, and millions slaves.

With what contempt must every eye look down

On that base, childish bauble call’d a crown,

The gilded bait, that lures the crowd, to come,

Bow down their necks, and meet a slavish doom;

The source of half the miseries men endure,

The quack that kills them, while it seems to cure.

Rous’d by the Reason of his manly page,

Once more shall Paine a listening world engage:

From Reason’s source, a bold reform he brings,

In raising up mankind, he pulls down kings,

Who, source of discord, patrons of all wrong,

On blood and murder have been fed too long:

Hid from the world, and tutor’d to be base,

The curse, the scourge, the ruin of our race,

Theirs was the task, a dull designing few,

To shackle beings that they scarcely knew,

Who made this globe the residence of slaves,

And built their thrones on systems form’d by knaves–

Advance, bright years, to work their final fall,

And haste the period that shall crush them all.

Who, that has read and scann’d the historic page

But glows, at every line, with kindling rage,

To see by them the rights of men aspers’d,

Freedom restrain’d, and Nature’s law revers’d,

Men, rank’d with beasts, by monarchs will’d away,

And bound young fools, or madmen to obey:

Now driven to wars, and now oppress’d at home,

Compell’d in crowds o’er distant seas to roam,

From India’s climes the plundered prize to bring

To glad the strumpet, or to glut the king.

Columbia, hail! immortal be thy reign:

Without a king, we till the smiling plain;

Without a king, we trace the unbounded sea,

And traffic round the globe, through each degree;

Each foreign clime our honour’d flag reveres,

Which asks no monarch, to support the Stars:

Without a king, the Laws maintain their sway,

While honour bids each generous heart obey.

Be ours the task the ambitious to restrain,

And this great lesson teach–that kings are vain;

That warring realms to certain ruin haste,

That kings subsist by war, and wars are waste:

So shall our nation, form’d on Virtue’s plan,

Remain the guardian of the Rights of Man,

A vast Republic, fam’d through every clime,

Without a king, to see the end of time.

Perhaps the most obvious aspect of this poem is Freneau’s support of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791), which basically argued that political revolution by the people is allowable when a government is not safeguarding the natural rights of its people. In particular, Paine wrote this book in order to defend the French Revolution. Freneau himself was an avid supporter of the French Revolution, holding a major grudge against the Federalist Alexander Hamilton while working as translator for then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Following Paine, Freneau posits a set of natural rights inherent to all “men” that all monarchies, by nature, fall to protect. I’m interested in Freneau’s linking of morality to political and national policies. Although Paine’s book specifically was written to support the French Revolution, Freneau brings in the United States, referred to here as “Columbia,” in order to celebrate the new US Constitution that will protect all citizens, including the common person.