Background

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Nature” was published by James Munroe and Company in 1836. It was controversial to some who criticized Emerson’s transcendental beliefs, however, it also became a highly influential text. For example, Henry David Thoreau read “Nature” while a senior at Harvard College and eventually wrote Walden while living in a cabin on land that Emerson owned. “Nature” is also considered the text that first presents Emerson’s transcendentalism.1

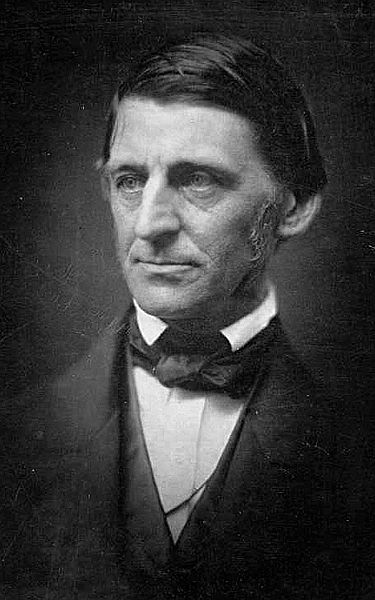

Portrait of Emerson, 1857

Summary

In an attempt to provide a solution, Emerson discourses about the problem that humans don’t fully appreciate and accept nature’s beauty. According to Emerson, people are distracted by the trappings and demands of society and cannot truly receive nature’s many gifts for this reason. He organizes the essay in eight sections: Nature, Commodity, Beauty, Language, Discipline, Idealism, Spirit, and Prospects.

Emerson argues that, in order to fully receive the benefits of nature, humans must entirely separate themselves from the distractions and demands of society. It is only through this situation that we can hope to experience the “wholeness” with nature which we were naturally meant to enjoy. He believes that “solitude” is the only state that would allow humans to experience this wholeness. Even items like books would prevent one from being truly in solitude. The wholeness which humans can experience in their true relationship with Nature is a spiritual relationship for Emerson, one that allows humans to become their ideal selves.

Notes & Quotes

- In describing Nature’s spiritual effect on humans (who commune with nature in a state of solitude), Emerson uses language that is positive, yet could easily be made subverted into the gothic mode. Poe, for example, often includes atmospheres and environments that influence, penetrate, and destabilize his human characters in his short fiction. Emerson, however, describes the natural environment as having the ability to “enchant,” “creep on,” and “persuade” us. For Emerson, rather than destabilize mankind, his Nature has the ability to “heal” us and make us better than society could:

-

The tempered light of the woods is like a perpetual morning, and is stimulating and heroic. The anciently reported spells of these places creep on us. The stems of pines, hemlocks, and oaks almost gleam like iron on the excited eye. The incommunicable trees begin to persuade us to live with them, and quit our life of solemn trifles…These enchantments are medicinal, they sober and heal us.

- Emerson also discusses the various benefits and gifts mankind may receive from his (or her) relationship with Nature. Again, his very positive sentiments could be subverted into the gothic mode, and present a different mode of looking at a similar subject. For example, Emerson describes mankind’s parasitical relationship with nature, as well as our “penetration” into the beautiful body of nature. Emerson presents a female version of nature, first as a maternal presence, next as a sort of virginal lover:

-

We nestle in nature, and draw our living as parasites from her roots and grains, and we receive glances from the heavenly bodies, which call us to solitude and foretell the remotest future… We penetrate bodily this incredible beauty; we dip our hands in this painted element; our eyes are bathed in these lights and forms…Art and luxury have early learned that they must work as enhancement and sequel to this original beauty.

- Emerson explains how nature can operate as a barometer to test the goodness of men: until mankind becomes whole with Nature, Nature will appear “mocking” to “fallen” mankind.

-

The sunset is unlike anything that is underneath it: it wants men. And the beauty of nature must always seem unreal and mocking, until the landscape has human figures that are as good as itself. It there were good men, there would never be this rapture in nature…Man is fallen; nature is erect, and serves as a differential thermometer, detecting the presence or absence of the divine sentiment in man.

- Once again, I detect a moment in Emerson’s text that is clearly a positive notion to him, but could easily be turned into a gothic moment of dread. He claims that elements and the landscape of society (towns, cities, etc) are just as much a part of Nature as the wilderness is. His description of this concept paints an image of a penetrating Nature that imbues all. This reminds me of some of the research on American wilderness which I completed while working on my Lovecraft seminar paper. The idea that wilderness is not something that can be penned up and separated from civilization through clear, man-made boundaries is one that is common in American ecogothic texts. Yet, for Emerson, this idea is a comfort.

-

We talk of deviations from natural life, as if artificial life were not also natural… If we consider how much we are nature’s, we need not be superstitious about towns, as if that terrific or benefic force did not find us there also, and fashion cities. Nature, who made the mason, made the house. We may hear too much of rural influences. The cool disengaged air of natural objects makes them enviable to us, chafed and irritable creatures with red faces, and we think we shall be as grand as they if we camp out and eat roots; but let us be men instead of woodchucks and the oak and the elm shall gladly serve us, though we sit in chairs of ivory on carpets of silk.

- Briefly stated, transcendentalism argues that the divine (God) suffuses nature and that reality can only be understood through a true appreciation and relationship with nature. ↩