This is the time of the semester where I suddenly want to combine texts I’ve read for my different classes into a single project. The reading this week for my American Gothic independent study centered around Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and the chapter titled “The ‘Black Arts’ of Citizenship” from Russ Castronovo’s Necro Citizenship. While reading through both, particularly Castronovo’s text, I was struck by how similar his argument was to Katherine Hayles’s How We Became Posthuman, despite the fact that Castronovo discusses spiritualism and slave narratives in 19th century America and Hayles covers contemporary popular culture and science.

I’m writing this blog post in hopes that it will help me to trace through some of the connections between these three texts and to explain why these moments of contact are important.

The Posthuman Gothic

Before diving into these texts, I think it’s important to first define what I mean by “gothic posthumanism.” The gothic is traditionally concerned with the monstrous “other,” often represented by a nonhuman being. The posthuman gothic represents a fear of the destruction of the western-liberal human subject as a result of technology. Of course, as Micheal Sean Bolton notes, a horrific depiction of technology is not enough to merit the label of “posthuman gothic.” 1 Instead, he argues that

“The source of dread in the posthuman Gothic lies not in the fear of our demise but in the uncertainty of what will become and what will be left of us after the change… posthuman Gothic works focus on the horror generated as the human becomes incorporated into the machine, interfacing with and evolving into the technological other.” (3-4)

Posthuman gothic texts depict a version of humanity that has been terribly altered either externally or internally as a result of overwhelming technology.

Hayles and Castronovo

In her seminal 1999 text, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Infomatics, Katherine Hayles highlights a few of the anxieties inherent within the posthuman age. According to Hayles, reading about the potential future ability to “download human consciousness into a computer” was “a roboticist’s dream that struck me as a nightmare.” 2 Moving from this dream/nightmare, Hayles explains that her goal in writing this book is to prevent the repeated erasure of the body in discussions about cybernetics. 3

Hayles asks if it is possible for information to travel across mediums without changing.

Hayles insists throughout chapters one and two of How we Became Posthuman that “abstracting information from a material base is an imaginary act.” 4 In other words, information requires a medium in order for the information to exist. At the start of chapter one, Hayles asks, “Even assuming such a separation (mind from body) was possible, how could anyone think that consciousness in an entirely different medium would remain unchanged, as if it had no connection with embodiment?” 5 Pointing to Star Trek’s “Beam me up, Scotty,” Hayles posits that belief in the possibility of information to circulate unchanged across different mediums is popularly accepted within our current culture. Based on Russ Castronovo’s Necro Citizenship, I’d argue that this dematerialized dream/nightmare was also present in 19th century America.

In discussing the tensions brought upon abolitionism and the slave narrative by 19th century white spiritualism, Russ Castronovo also highlights the dangers in assuming that the soul or spirit (what Hayles terms “information”) can be easily separated from the body. Castronovo describes the white spiritual ideal as

“the nonsocial world of the spirit. By declaring irrelevant all the particulars that bear on bodies- weather, political systems, the cultural meanings of skin color- so as to pursue essence… the soul’s utopian capacity to liberate the body.” (163)

In the spirit realm, all souls are considered equal (although many spiritual texts of the 19th century still ascribed racial markings of voice and movement to the ghosts they encountered) and depoliticized. Castronovo explains that Abraham Lincoln supposedly carefully listened to the advice he received from the deceased Daniel Webster via Nettie Coburn Maynard, a female medium. Ghostly political advice was valued largely because of the belief that spirits represented “the disinterestedness that underwrites the ideal of rational public personhood. Without bodies, it is no skin off their noses to distribute resources to whites and blacks, presidents and slaves alike.” 6

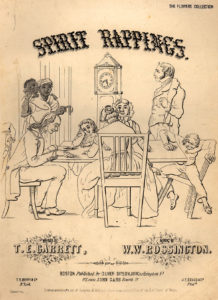

During 19th century American séances, various spirit “technology” was implemented, including ghost writing and spirit rapping. Ghosts could inhabit property and move it around, exemplified in Necro Citizenship by the “folksy” story of Lincoln sitting (and taking a ride) on a hyperactive piano. 7

Incidents and Gothic Posthumanism

At the end of Incidents, Harriet Jacobs’s Linda Brendt has achieved liberation in the North. Jacobs includes two visions of death with Brendt experiences after her freedom: the first being “tender memories” of her grandmother. This example of what Castronovo terms “spiritual liberation” 8 is positive and a comfort to the living Brendt. However, the second depiction of spiritual liberation is the news of the death of Brendt’s Uncle Phillip. Castronovo rightly describes the eulogy Phillip receives as containing “posthumous enfranchisement,”9 as Phillip is labeled here as “a useful citizen.” In the spirit realm where all, according to 19th century white spiritualism, are equal, Phillip is suddenly granted the right of citizenship. Although this is an example of finding liberation through dematerialization, it is of no use to Phillip, his family, or to the many other living black Americans who were still enslaved.

On the other hand, in writing her narrative, Jacobs quickly moves through her sexual experiences, refusing to allow a completely embodied representation to be presented to her voyeuristic (largely white female) readers. Jacobs’s Linda Brendt therefore exists somewhere in between the spiritual and material. Castronovo describes this as materializing the immaterial by embodying ghosts and their history. [ 10. pp. 195] By returning these spirits (or, for Hayles, “information”) back into corporeal bodies, they can be historicized, politicized, and protected from appropriation and mutation.

For Harriet Jacobs, to be rendered as pure information and completely separated from one’s body is something to be feared. To be dematerialized entirely is to be psychically owned by another, spiritually repeating the physical enslavement experienced during life. Spirits may only tell their stories through the medium of technology or through the body of a medium, who would either speak their story out loud for parlor guests, or write the spirit’s story down for publication. It is through this dematerialized change in medium (from black body to spirit technology/white medium body) that the slave’s identity, spirit, and memory is appropriated and altered.

Thanks, Caitlin, for this conjunction. I also like the broader contextualization around the idea of the gothic. In addition to being posthuman, the gothic is often post-expressive (“unspeakable horror,” “indescribable terror,” etc). Nice work. —Russ Castronovo

Thanks for your response and your thoughts. I think viewing the gothic as post-expressive as well as posthuman can be really helpful…