Thesis

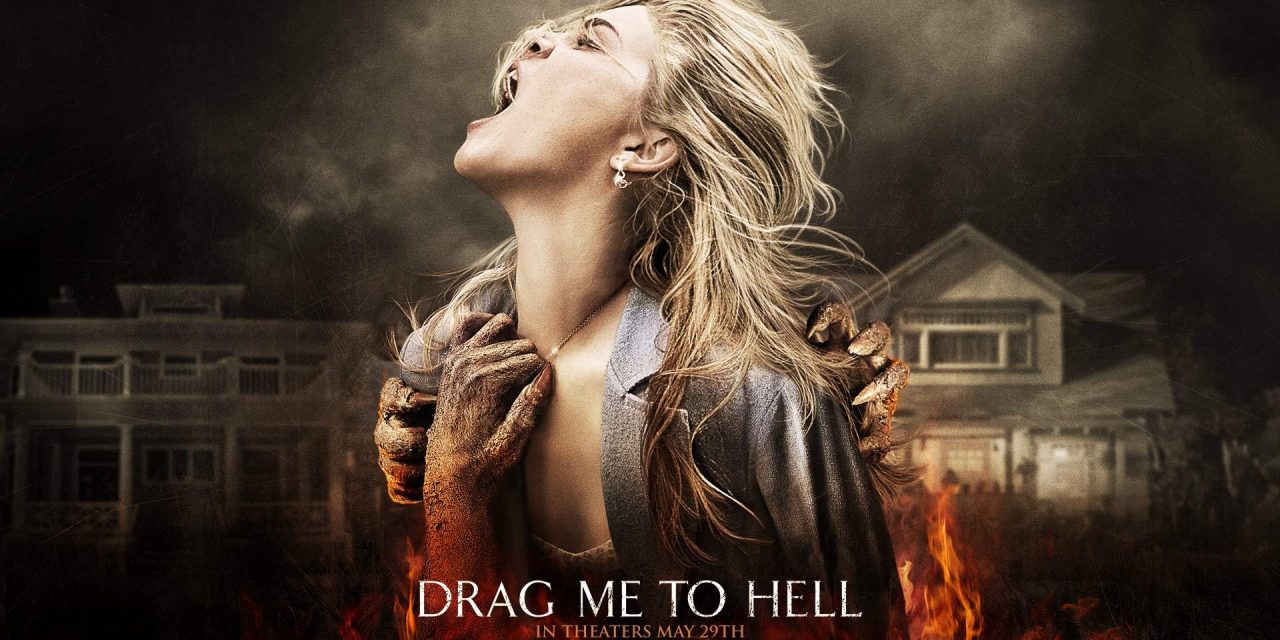

“Houses of Horror” from Annie McClanahan’s Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First Century Culture (2016) argues that horror films provide the perfect language for expressing our present credit economy “in which risk and fear are a source of profit” (182). She spends the chapter focusing on four films: Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell (2009), Pang Ho-cheung’s Dream Home (2010), Darren Lynn Bousman’s remake Mother’s Day (2010), and Josh Stolberg’s Crawlspace (2013), all of which do not merely allegorize the housing crisis and credit economy, but which place this issues at the center of their horror. Using these films, McClanahan explores this horror-infused discourse, “arguing that it does not merely reflect the fear associated with market volatility but also is an attempt to register historical transformations in the economy itself: the financialization of risky credit that preceded the crisis and the material experience of housing risk that followed in its wake” (143). Additionally, she explores the new meaning of appropriate payback, which she situates as best paid from the debtor to the creditor.

Notes & Quotes

- Repeatedly, McClanahan explains that debt works through fear rather than though a moral obligation. Instead, we are trained to fear “the material consequences of default…debt is frightening not because it produces shame guilt but because it opens up the possibility of economic precarity and vulnerability” (144). In order to function, the modern credit economy insists that its a “form of exchange based on trust, confidence, and social cohesion depended on credit’s separation from both the language and the logic of vengeance” (176). McClanahan, however, proves this to be an empty ideological promise that merely helps citizens to accept the multiple forms of violence that is enacted on debtors and other precarious populations in order to support the interests of corporations and the wealthy elite. This violence includes homelessness, the robbing/denial of sentimental ownership, and the destruction of the self (property and the home become part of the individual). Because fear and violence are so integral to this economy and modern-day real estate, vengeance is the natural reaction. In Drag Me to Hell, she notices an argument for the debtor’s violent revenge on the plundering creditor/bank (Christine). This is also present in the home invasion film Mother’s Day, where the film ends with the possible future revenge on Beth, who also functions as bank and creditor. I think a really interesting aspect of the films McClanahan selects for this analysis is the fact that both films make the “true” villain appear to be more like Clover’s final girl. It is only through the final scene and through moments of sympathy for the seemingly monstrous characters (in Drag Me, Mrs. Gamush and in Mother’s Day, the Koffin family). Does this point to the spectral nature of the credit economy and present-day real estate, which operates through extreme liquidity? Or is this depicting the mask that banks and loan officers like Christine often wear, presenting credit and mortgages as exciting ways to have capital even when you are cash-poor. The various euphemisms used by banks (“debt restructuring” is the term Christine uses to describe how she will “help” a company to get into more debt in order to grow), as well as the way the credit economy and speculation has been instilled into our society as American values might also work in a similar way: wearing the mask of the hero, despite having the actual status of the villain. Finally, it could also point to the way that a good portion of the American population (and probably most of the horror film audience) is complicit in the violence of debt and speculation. We see the film through the eyes of the villain just as we continue to live in repossessed houses or gentrified neighborhoods. Christine is certainly monstrous, but I think she only gets there because of her acceptance of capitalist culture and values. In order to be considered a valued employee of the bank, she needs to put aside her humanist feelings and sympathies for people like Mrs. Ganush and instead focus on supporting the greedy and poisonous desires of the bank.

- McClanahan also describes the spectral nature of credit, as opposed to material reality of property (like homes) or earlier conception of money (cash, the gold standard, coins, etc.). The speculative risk attached to the credit economy leads to material precarity (147). I’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between spectral credit/identity and material life through the survival game subgenre. I’m happy to see that similar questions are being raised in the “houses of horror” subgenre. In the final shot of Black Christmas (1974), we are shown the opulent home, warmly decorated for the holidays. However, because the audience has just seen the film, we know that this house is also a crime scene. There are bodies inside of it. However, the house continues to stand for wealth and the American dream of comfort and property. Although this film is from the 1970’s and therefore, according to McClanahan, focuses on low growth and high inflation (149), I am reminded of this filmic moment through McClanahan’s discussion of material results of spectral credit because of it’s representation of the endurance of value. There is a section in this chapter where McClanahan notes that a house can have a public or criminal stigma (as well as a phenomena stigma if it’s haunted) that can drastically lower its value (160). Cases of disclosure fraud may therefore occur by realtors who fail to properly disclose to purchasers any property stigma associated with the house in order to get the property a higher value (161). In this shot of Black Christmas, we see nothing but the valuable property and the American dream, but are refused any reference to the dead bodies located inside. Additionally, a beautiful house full of bodies is a great visual to represent past occupants violently foisted from the home. The spectral presence of property stigma is forever present. This can also be seen in other 1970’s films like The Amityville Horror and The Shining, as well as more recent films like The Conjuring series. Additionally, haunted house films repeatedly enact spectral violence against material bodies. Because of market liquidity, real estate, despite its inherent materiality and immobility, has become a spectral and violent market fueled by fear (often in horror films, characters are advised to not react or “mess with” the ghost or demon, stating that it feeds off of fear).

The final shot from Black Christmas

- I was also really interested in McClanahan’s discussion of the shifting perception of ownership. In the post-crisis, debt-driven horror film, new owners are often terrorized by past owners, who claim ownership, despite foreclosure, due to the fact that they have a sentimental or labor-focused right to the home. The guilt of these new owners, as well as the payback that ensues, comes from their sudden revelation that they may not truly own the house, and therefore risk invasion (from inside the house). In 1970’s haunted house films, ownership of property is made terrifying because of the high inflation and low growth of their contemporary economy. In the 19th century, American haunted house literature (Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables is exemplary here) typically wrestles with their own questions of ownership. In Seven Gables, the Pynchon family owns a house that was wrongfully (but legally) taken from the working class Maule’s, which was built on land that was wrongfully (but legally) taken from the American Indians. McClanahan also noticed something similar at work, stating that the post-crisis house horror film often echoes historical wrongs and questions of ownership and property.

- I wonder why McClanahan doesn’t include any post-crisis haunted house films. The closest she gets to this is her inclusion of Drag Me to Hell, but, although this includes a vengeful ghost, it’s not a true haunted house film. I believe that Paranormal Activity (2007) would’ve been a great addition to her list of films. Perhaps I’ll focus on this film and its connection to Dead Pledges as part of my haunted house question. Once again, it directly engages with the credit market, not only through the fact that it takes place in a new, opulent house (and therefore, according to McClanahan in her use of Frederic Jameson’s quote), displays a “longing for history” (178). With houses torn down in order to build new, more valuable homes for new buyers, it’s difficult to find a house with a true past, which in turn makes it difficult to work under the generic haunted house elements, which typically relies on a house with a past. Katie, an English major, instead brings the ghost with her from her childhood home, which burned down. Again, we see a spectral sort of debt or credit invisibly attached to a main character and causing her material violence. Her live-in boyfriend, Micah, is a day-trader, a job which, according to Forbes, requires a lot of risk-taking, quick maneuvering, as well as a “stomach” for gambling when the odds are stacked against you. Upon hearing Katie’s story that she has a ghost (demon) attached to her, he becomes very excited and happily chatters about “what they can get” from capturing paranormal footage on camera. The Forbes article I cite earlier’s title asks whether day-trading is “Smart or Stupid,” which perfectly matches with Micah’s behavior. He never questions whether the paranormal is real or not, but instead dives headlong into capturing the spectral for his own gain. Additionally, it seems like that demon is living in the couple’s attack after they trace hoof-prints to the attack door, which is mysteriously open. Micah immediately goes up to investigate (classic stupid horror film move, but maybe fits with his skills as a day-trader, as well as his strongly held belief in his own ownership of the property and his desire to defend his home and “his” girl even when she begs him to stop because what he does is harmful and serves primarily only to fuel their own fear which in turn energizes the demon) and finds a burned piece of a photo of young Katie that could not have survived the fire that burned down her childhood home. Once again, the threat comes from inside the house rather than an invasion from the outside.

- I also think that the recent adaptation of The Haunting of Hill House would be interesting to explore through Dead Pledges. Unlike Shirley Jackson’s original 1959 novel, the 2018 television series follows the Crane family, who purchased Hill House in the 1990’s with the intent to briefly live in it, flip it, then sell it for a profit. Unfortunately, the house refuses the Crane family’s speculation and prevents any restoration from happening (there is an extremely bad black mold problem that refuses to be fixed). The series moves back and forth between the 90’s and present-day. In the scenes from the present, we learn that the Crane family never sold the house (the children, as well as the audience, believe that it was unable to be sold, but we eventually learn that the father, Hugh Crain, agreed to neither sell it nor burn it down, in order to protect future owners from danger. He denies the home its contagion (unlike Drag Me to Hell), but in the end, he and his family must pay their debt to the house, returning to it, dying, and joining the other spirits.

After being forced from Hill House, Hugh Crane places his children temporarily in a hotel.