In his article “Narration, Intrigue, and Reader Positioning in Electronic Narratives,” Daniel Punday introduces readers to Espen J. Aarseth’s definition of “intrigue”: “a sequence of oscillating activities effectuated (but not controlled) by the user” (25-26). Although these are actions taken by the reader “to move the game forward,” successful digital text (including video games) designs ensure that these moves are controlled by the text’s creator/author. To this, Punday adds that “all forms of textuality that require the user to act” depend upon the player’s ability to intuit both the values of the fictional world as well as the rules of the text (29, emphasis in original). While the designer of the video game or digital text chooses a “domain or fictional setting” first, then creates rules which fit the genre or theme (Ibid.). Punday notes that, for the reader or player, this process is inverted: users learn the rules through assumptions they can make based on the text’s narrative world (Ibid.). For this blog post, I will follow Punday’s example and examine both a digital text and a video game in order to determine the interactions present between the rules and the narrative. My selection of digital text, Welcome to Pine Point (2011), allows me to analyze the outcome of a digital narrative experience in which the reader must obey the rules, while my selection of video game, Friday the 13th: The Game (2017), will allow for the exploration of what happens when users don’t necessarily have to learn or play by the rules.

Welcome to Pine Point (2011)

Welcome to Pine Point is an interactive digital documentary created by Michael Simons and Paul Shoebridge (AKA: The Goggles) in 2011. The multimedia film focuses on the memories of former residents of Pine Point, a mining town in Canada which no longer exists. Simons has a personal connection to Pine Point which is explicitly mentioned in the film’s first bit of text: “Pine Point was the first place I ever went alone.”

By clicking on the “About This Project” tab, readers can learn about the creation of the documentary. Apparently, it was originally meant to be a print book that focused on “the death of photo albums as a way to house memory.” At the end of the “About This Project” text, they note that, although Welcome to Pine Point could have been a book, “it probably makes more sense that it became this.” I couldn’t agree more.

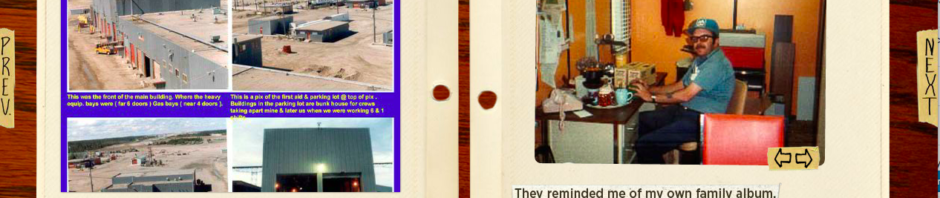

The focus on memory and the methods people use to preserve these memories (ie, photo albums) comes across clearly to the reader while he or she moves through the digital narrative. It incorporates a number of different media, including photographs, illustrations, video, music, voice-overs, and text, all which come together to create a sort of video collage. It’s immediately reminiscent of earlier photo albums, a method of remembering which the citizens of Pine Point may have maintained during the 1970’s or 80’s. Because of its clear genre, readers learn the rules by which they can correctly move the narrative forward (or engage in the intrigue). Sections of the film progress by the reader click the tab to the right, marked “NEXT” (alternatively, readers could click the tab on the left marked “PREV.” to move backwards in the narrative). These tabs, as well as  much of the text embedded in the film appear like words written with a thin Sharpie marker on yellowed paper or tape. Photos within the film are often part of a set. Just like in a photobook, users can flip through the images to view them all. Although the reader must “act” by clicking through numerous media, including the tabs and images, the creator still maintains ultimate control. In fact, this is an extreme example of creator-control: the narrative can only follow one path, as evidenced through the fact that the entire video can also be viewed on Youtube (however, this does not provide the same experience).

much of the text embedded in the film appear like words written with a thin Sharpie marker on yellowed paper or tape. Photos within the film are often part of a set. Just like in a photobook, users can flip through the images to view them all. Although the reader must “act” by clicking through numerous media, including the tabs and images, the creator still maintains ultimate control. In fact, this is an extreme example of creator-control: the narrative can only follow one path, as evidenced through the fact that the entire video can also be viewed on Youtube (however, this does not provide the same experience).

A nostalgic atmosphere is effectively present throughout the film as a result of the dual successes of the intrigue and the narrative. The story of a mining town which no longer exists, as well as the lives of a number of its inhabitants, unfolds via the nostalgic re-rendering of the photo album (perhaps there’s a connection here to Lisa Blackman’s “Haunted Data” article?) all while soft music plays in the background. Sometimes the sound changes to voice-overs, or atmospheric noise like glasses clinking and joyous voices rambunctiously chatting. Through all of these methods, the past can return to the present, creating a digital space for Pine Point to once again exist. This is especially notable due to the fact that the documentary was originally inspired by a web site that a collection of Pine Point citizens created, “Pine Point Revisited.”

By playing by the rules (clicking through the tabs and photos, reading the text, and ensuring that the computer’s sound is turned on), users are guided by the text’s intrigue to experience the narrative and the resulting feeling of nostalgia.

Friday the 13th: The Game

The recent Friday the 13th game is based on the 1980 film of the same title. It was developed by IllFonic, and published by Gun Media for PS4, Xbox One and  MicrosoftWindows. Friday the 13th: The Game is an asymmetrical multiplayer game featuring a semi-open world. This means that up to seven players can play as the teenaged counselors who must survive the vengeful murderous rampage of Jason Voorhees, controlled by an eighth player. Despite being a horror game, it does not employ directed navigational direction and instead allows characters to roam freely throughout the virtual Camp Crystal Lake. Although the players can move when and where they’d like, there are certain tasks that each player must fulfill to win the game. While Jason’s objective is to kill all of the teenagers, the counselors must avoid Jason to survive or escape the camp grounds all while locking doors, finding weapons, and using a radio to call for help. Friday the 13th has a soundtrack similar to one that might be used in a horror film and when Jason comes close to a counselor, loud aggressive music plays, serving to both warn the players and to heighten the players’ fear.

MicrosoftWindows. Friday the 13th: The Game is an asymmetrical multiplayer game featuring a semi-open world. This means that up to seven players can play as the teenaged counselors who must survive the vengeful murderous rampage of Jason Voorhees, controlled by an eighth player. Despite being a horror game, it does not employ directed navigational direction and instead allows characters to roam freely throughout the virtual Camp Crystal Lake. Although the players can move when and where they’d like, there are certain tasks that each player must fulfill to win the game. While Jason’s objective is to kill all of the teenagers, the counselors must avoid Jason to survive or escape the camp grounds all while locking doors, finding weapons, and using a radio to call for help. Friday the 13th has a soundtrack similar to one that might be used in a horror film and when Jason comes close to a counselor, loud aggressive music plays, serving to both warn the players and to heighten the players’ fear.

The teenage-slasher film, a sub-genre of horror, has always incorporated “rules” into its narrative. These rules are typically incorporated to support a conservative world-view (ie: don’t have sex, don’t drink alcohol, etc), however, they provide an easy “in” for video games of the genre to include rules. Oddly enough, as is clear through my brief description of the game, Friday the 13th: The Game has VERY few rules. While this may add to the enjoyment and excitement a user may feel while playing the game, a lack of rules or clear intrigue can serve to drastically alter the narrative. It is for this reason that designers may want to ensure their control of the narrative via strict rules.

One challenge of Friday the 13th resulted from the game’s lack of depth and the fact that the game allowed players too much freedom in their movements and choices. Soon after the game’s release, legions of self-proclaimed “teamkillers” complained about the repetitiveness of the game and, instead of focusing on escaping or killing Jason, began to  purposefully kill the other counselors.1 This not only destroyed the narrative, but it also drastically altered the affective power of Friday the 13th as a horror game. The sense of control players have over their character can create a sense of empathy for that character and his or her other teammates in the game. This allows the player to identify with their character, creating a deeper sense of dread or fear when their character is in danger.2 Clearly, this was not the experience of the many “teamkillers” who stalked the virtual campgrounds of Friday the 13th for their unsuspecting prey. Rather than feeling fear, players began to experience frustration.3

purposefully kill the other counselors.1 This not only destroyed the narrative, but it also drastically altered the affective power of Friday the 13th as a horror game. The sense of control players have over their character can create a sense of empathy for that character and his or her other teammates in the game. This allows the player to identify with their character, creating a deeper sense of dread or fear when their character is in danger.2 Clearly, this was not the experience of the many “teamkillers” who stalked the virtual campgrounds of Friday the 13th for their unsuspecting prey. Rather than feeling fear, players began to experience frustration.3

- Ponder, Stacie. “In Friday the 13th, the Real Killer isn’t Jason- It’s Your Teammates!” Kotako ↩

- Madigan, Jamie. “The Psychology of Horror Games.” The Psychology of Games, October 29, 2015. ↩

- This has since been “patched,” but there are still major issues with the game. For more, see Stephen Wilds’s “Friday the 13th Team Killing Change is Welcomed, But Larger Issues Still Persist.” ↩

This is such a great application of the intrigue concept! It hadn’t occurred to me before, but intrigue might be, in a way, inversely connected to the idea of literary affordances. What do you think? The more intrigue a text has, the more motivation a user has for participating with the creator of the text (for following the creator’s direction), but without intrigue, users are more open to using the text as they see fit.

Hi, Caitlin!

I think the importance of rules within a narrative depend on the author’s or creator’s reason for creating the narrative. For instance, Welcome to Pine Point was created as a remembrance of a vanished town. It exists as an interactive historical marker, the way those plaques along highways do. With a video game, the story is important in order to give the player an immersive experience, but the reason a video game exists is to have the player complete a goal of some kind. Games need rules or else what’s the point of playing?

In the case of Friday the 13th, I think what happened is that the the players usurped the goal the video game designers had in mind. To a teamkiller, winning the game is a matter of killing the team, and a way was found to do that. This brings up the question of who really is the author of a digital narrative? Welcome to Pine Point has many collaborators, but as you said, the user going through the documentary has very set tracks to follow. Video games, however, used to be that way, but then sandbox games came along and changed that. One version of Friday the 13th exists, but how people play it changes its narrative. And with Let’s Play videos that people post on YouTube, the rest of the world can see that narrative.

So many fantastic points here. It is interesting how elegantly Blackman’s essay on hauntology and Punday’s essay with its emphasis on intrigue and rules. You are right to point out that the rules set up by the author are achieved through inversion for the player/reader/user. I feel enriched by this discussion, and it has helped me with my own research and readings on Poppy. I’m going to approach it from hereon out as transmedial storytelling driven by intrigue and hauntology. I’ve seen people construct meta-theories about Poppy being a millennial marketing scheme, and of course, it could be that as well (I think it is). This makes me want to find a connection between viral marketing and creativity and storytelling; obviously, there has to be a point where viral marketing breaks with creativity entirely, and others where it is almost entirely driven by good storytelling.

When we talk about games in a week, we can relate it to James Paul Gee’s article about “Good Video Games and Good Learning,” http://jamespaulgee.com/pdfs/Good%20Games%20and%20Good%20Learning.pdf

which lays out a schema for learning that involves learning the rules of games through discourse communities/teamwork and “just in time” learning. I would say that this also could be related to the narrative rules described by Punday–giving players/readers/users a path to discoveries created through community ties creates engagement, fun, and a sense of empowerment. In the situation of teamkilling, someone’s sense of all these things can be disrupted to the point that some players cannot play at all. And in some situations, issues of real world discrimination (as toward females and POC, or toward the inexperienced player) creep in.

Kudos on your excellent analysis of Pine Point. I love the audio–love the whole presentation but the audio especially is a “haunt” for me. When you hear Richard’s audio instructions “mouse click” at the beginning, it is simply strange noise which by the end achieves tremendous power as part of the story. I felt a somewhat similar power in Jon’s video–if you haven’t seen it, check it out on his blog–as the story moved from a fun, seemingly simple memory about visiting a haunted house to a multilayered, rich story about multiple selves and persistent ties to the past.